The November member call featured the work of Mats Alvesson from Lund University in Sweeden. To listen to the recording of the call, click the following link: Listen to November LILA Member Call

The November member call featured the work of Mats Alvesson from Lund University in Sweeden. To listen to the recording of the call, click the following link: Listen to November LILA Member Call

- How do people react to significant organizational change?

- Do we see ourselves as helping change to come about, or allowing change to happen around us?

- How can we adapt more easily to change?

- See organizational transformation as a matter of self-transformations including everybody, not just those to be ‘worked upon’ for improvement.

- Work with moderate (realistic) aims and proceed from the experiences of existing culture, realizing that only some progress can be made within the near future.

- There is a need for endurance and a long-term view.

- Cultural change work calls for accepting the need for integration of conceptualization and implementation and on-going follow-up work.

- It is important not only to manage and clarify the roles and relationships between those engaged in change work but also to address their identities.

- Equally important, and related to identity clarification, is the theme of developing and, when called for, revising the basic image of the change program.

- There is a need for a strong sense of a ‘we’ in change work – if those promoting and seen as symbolizing the cultural change are viewed as outsiders or on the periphery of an organization, then the change project’s credibility and experienced relevance will be questioned.

- Focus on meanings, rather than – or at least more than – values.

- Combine pushing and dialogue.

-

Working with organizational culture calls for skillful work with emotions and symbolism– the formulation of messages that appeal not only to reason and intellect but also to emotion and imagination is important.It is important to take seriously the local sense making that takes place in organizations during change.Detailed Documentation from the call

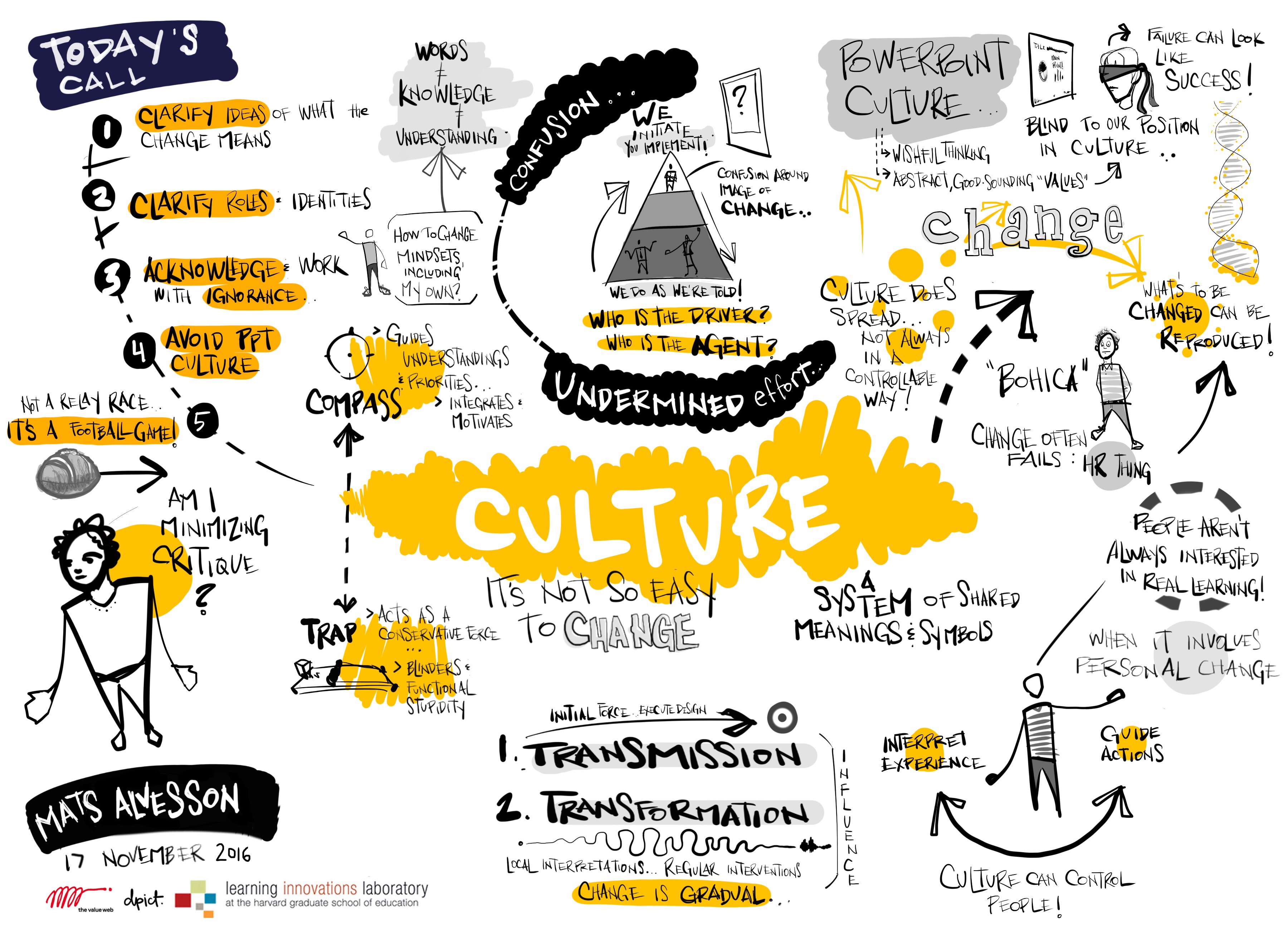

Professor Alvesson called to tell us about a case study he did of a culture change initiative at a large technology firm in Sweden.

First, what is culture? It is a system of meanings and symbols shared by members of a collective; or “Culture is the creation of meaning through which human beings interpret their experiences and guide their actions” (Geertz, 1973). But it’s easy for organizational leaders to think of culture as a mission statement or management slogans, what Mats calls “PowerPoint culture.”

But culture is really what guides our guides our understandings and priorities. It integrates and motivates. That means it can also be a conservative force, because it constrains what we see and don’t see. This can lead to blinders and functional stupidity (box thinking).

However, managers often focus on “PowerPoint culture” when they want to create cultural change, citing wishful thinking, abstract, good sounding ’values’ like “customer-focused” or “culture of innovation.” This PowerPoint culture often becomes disconnected from experienced and real culture. The real culture is usually hard to verbalize and even hard to see.

Culture change projects often fail: they are experienced as another ’HR thing’ or a consultant’s fancy project. It’s a feel-good exercise for management, some staff, and consultants. But for the rest of the organization, it can feel like “bohica” – bend over, here it comes again. If there are too many of these initiatives without follow-through, the culture becomes even more resistant to change.

Mats then explained more about the case study, on a former R & D unit (1000 employees) in large high tech firm that was becoming an independent firm (subsidiary). This unit was perceived to have problems with a too strong technology orientation, weak and invisible leadership, and insufficient teamwork.

Top management created a program aiming for cultural change, meant to instill new values:

- Outstanding customer relations

- Inspirational leadership

- Strong teamwork

Top management was involved and engaged, and the program was designed by consultants from large consultancy firm (with quality check by other consultants). Lots of resources went into the program, including a kick-off, management talks, a management club, workshops, documents, video, tool kit with exercises, etc.

However, when Mats and his team interviewed the junior managers and employees, they said that nothing happened, nothing changed, it was ‘paper and talk’ and ‘bread and spectacle for the people.’ Why?

Mats notes that there was a fundamental confusion around the basic image of the change project:

- Expectation that this was meant to be a transformation of the company

- This was the expectation of junior members

- The start of new practices, new behaviors that would be dictated as part of the initiative

- A management-driven push to create and instantiate change

- “we do as we are told (tick off tasks); waiting for top management to act as the key driver”

- Expectation that this was an eye-opener

- This was the expectation of senior management

- Assume that once people’s eyes were open to the need for culture change, they would spontaneously begin to behave differently, without the need for more guidance

- Another metaphor: the wave, like at a sporting event. The insight would spread from person to person naturally

- “we initiate as the architects, and the middle managers will implement and act as culture carriers and change agents”

So who was meant to be the central change agents and central drivers of the change was unclear and resulted in confusion and resistance. This relates to the issue of identities and ’meta-meanings’ in change work. There was disagreement around

- the overall meaning of the project;

- their own situated identities, e.g. how they defined themselves in this context;

- ascriptions of positions to others (roles); and

- their own models of how the organizational world looked and their own (limited) place in it.

The result was that the implicit culture already in place in the organization took over. What was to be changed became reproduced. The non-visible leadership and distrust in management, limited teamwork, and focus on technology all continued and even got more entrenched. This is how culture can be a trap.

Mats shared some lessons that came out of the case study:

- Choose carefully and commit fully

- If you can’t follow through with a change initiative and really invest what you need to in it, not only will you not succeed, you will create resistance to change in the future

- Clarify ideas of what the change initiative means

- In this case, some people expected substantive change and others expected the generation of insight

- Without a shared meaning, the initiative went nowhere

- Clarify roles and identities

- In this case, HR really thought that their role was to act as a post office – relaying messages from top management to the staff

- But top management thought HR should act as change agents

- In this case, they didn’t even realize they were confused, and everyone was disappointed in everyone else

- Acknowledge and work with ignorance: people can say the words but have no clue

- A common slogan was “our customers come first,” and Matss observed a meeting where people were discussing what this meant, and people were unsure and disagreed

- Don’t assume that people know what the words they use mean

- g. sustainability, leadership, trust, strategy etc. can be meaningless if they are not clearly defined with relevant examples

- Avoid PowerPoint culture: work with cultural meaning in practice

- Work with the concrete practice—e.g. closely examine how we run meetings to reveal habits and patterns, to reveal culture.

- Use what is happening on the ground to illustrate the culture, so people can connect their actual behaviors with the words on the page.

- See change not as a relay race, but football game

- Relay race

- In this case, each leadership tier viewed their part of the process as a relay race.

- You run then hand the stick to the next person and then they hand it on. When you are done, your task is over, and you stop running.

- Top management designed the initiative and handed it over to HR who explained it to the middle mangers who were supposed to implement it.

- This approach means that no one was tracking the whole process from start to finish at all levels.

- Think of it as a football game instead

- See the big picture, compensate for others’ moves and reactions as they unfold.

- Relay race

Finally, Mats shared two views on the exercise of influence. Top leaders viewed the change as transmission: you apply a strong initial force, in the form of an execution of a design and a launch, with the expectation that an outcome will follow. However, messages are always transformed when they are sent out. Messages and ’forces’ are always interpreted and translated locally. As initiatives are rolled out, ’shit happens’ and leaders need to adapt their message as it goes. Senior people need to follow closely and intervene regularly.

Questions and answers

How successful did people think this initiative was? Senior leadership saw it as reasonably successful, which was totally different from all the junior people we interviewed. When we told the senior leadership about this, they distanced themselves and tried to bury their mistakes rather than learn from it.

Were you able help the senior leadership team with that? That wasn’t our role as researchers.

We find in general, people are not interested in learning if it calls for revisions of their own frameworks or recognition of their own mistakes or problems. The knee-jerk reaction is usually “others need to change.” A culture of positivity can also lead to a failure to learn from mistakes, because people feel that they shouldn’t dwell on the past and simply move on.

Why didn’t the change spread through “the wave” or contagion like senior management thought that it would? People do mimic others, but it’s not very predictable. We think that the messages coming from senior leadership will be at the top of the hierarchy of ideas, but other factors are influential too, sometimes more so. People are influenced by mass media, fashion, ideas they’ve read, etc. Imitating can work, but is often the spreading of the words, but not the thinking or meaning behind them.

Would it have helped to time-bound the change process? Change certainly does take a long time, and a lot of stamina. People usually quit or move on too soon. In this case, they launched another initiative about faster delivery timelines just one year later, and it was in conflict with the cultural change initiative, which only made it worse.

It seems that clarifying roles and identity is important, but people hold on to those steadfastly. Often they need to unlearn past approaches. What is your experience when a person’s identity is connected to the old culture? Identity is very important. In this case, the identity shift should have been about expanding middle managers’ mindsets from “I implement a to-do list” to a much broader, more expansive view of their role in company. They needed to take on the need for the change and buy into it. An example from a different case was scientists in pharmaceuticals; the metaphor they identified with was “research scientists” interested in creating new knowledge. But they were encouraged to change their identity to “drug hunters” which helped them be more efficient.