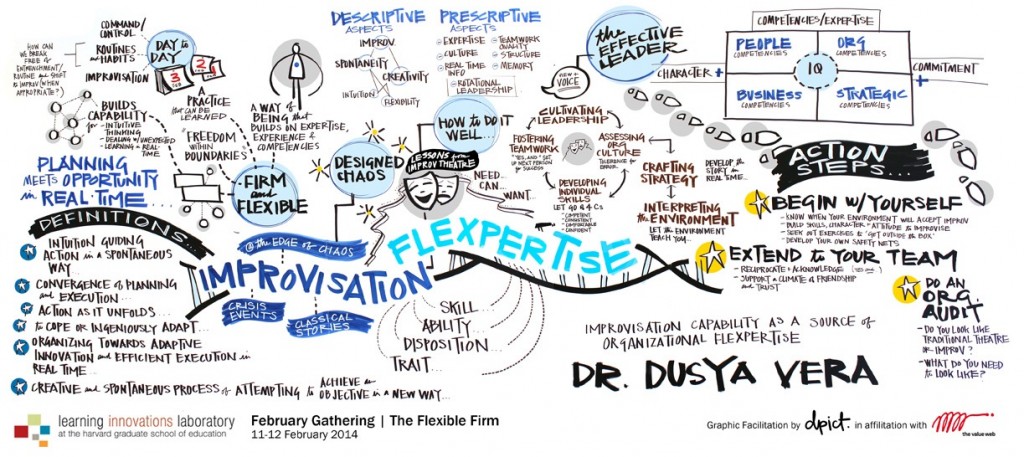

In the LILA October 2014 meeting, we argued that flexible experts have certain skills and abilities, dispositions, traits, metacognitive and self-regulatory skills, and experiences. Dr. Vera suggested that improvisation is one of those competencies that people develop at an individual, a team, or an organization level. She began the lecture by proposing the following questions: Is it enough to have a few people improvising? Or do you need an entire organization to improvise?

Growing up in South America, Dr. Vera noticed a lot of improvisations happening around her. Given the political, social, and natural environments, planning or predicting within the next three months or a year was difficult in Ecuador. In many ways, one had to improvise through life. It was not until Dr. Vera began her Ph.D. she learned that improvisation can be a complementary skill to planning. The question then becomes, how do we learn to improvise effectively and productively?

Dr. Vera suggested three questions to consider for the LILA conference:

• How can organizations be both firm and flexible?

• What organizational factors support a strategy of “designed chaos”?

• Quality and effectiveness: how can organizations improvise in the face of time pressure, ambiguity and uncertainty?

She proposed several definitions of improvisation. Improvisation is the intuition guiding action in a spontaneous way. It is the convergence of planning and execution. It is the conception of action as it unfolds. To define improvisation as coping or ingeniously adapting to a set of circumstances, however, is to presume the ability to cope well. Improvisation is the creative and spontaneous process of attempting to achieve an objective in a new way. If you are an improviser or a flexpert, you are called to apply expert knowledge flexibly and effectively to nonstandard situations, changing circumstances, and the unknown.

Improvisation sounds like freedom, but there are boundaries. It is a way of “being” that builds on expertise, experience, and competency while not being imprisoned by them. Think about actors, jazz musicians. They need expertise to do it well. In jazz, improvisation involves reworking precomposed material and designs in relation to unanticipated ideas. The musicians don’t have time to stop and think. That’s where flexpertise differs from improvisation in that one can take time to be a flexpert. Improvisation, on the other hand, is a type of learning in real-time.

Many people think that improvisation works only in the arts. In fact, improvisation is a practice that can be learned through trial-and-error in everyday work. Improvisation is also a core source of resilience. Through improvisation, one can bounce back more nimbly.

To pretend that improvisation is not happening in organizations is to not understand the nature of improvisation. Sometimes, improvisation is seen as not responsible because it implies mistakes, risks, and loss of control. But people in organizations are often jumping into action without clear plans, making up reasons as they proceed, discovering new routes once action is initiated, proposing multiple interpretations, navigating through discrepancies, combining disparate and incomplete materials and then discovering what their original purpose was.

Improvisation involves spontaneity and creativity, which can benefit your personal and professional life. Implicitly, it also involves intuition and flexibility. In terms of its prescriptive aspects, expertise, memory, structure, real-time information, teamwork quality, culture, and rotational leadership (giving the leadership to the person that has more expertise at hand) are contexts that affect improvisation.

Second City developed a package of training that combined theater improv with strategy. To translate lessons from Second City into strategic development, you need to think about 1) what you need to do; 2) what you can do; and 3) what you want to do. The first one defines the crafting of the goal of the strategy (exercise: each actor says one word at a time to build a story). The second one teaches you to open your mind to let the environment teach you and to not let too routines and expertise bound you. (exercise: go through a room and call the items you see a different name than it is before discussing how to be open to things that we are not seeing).

In order to develop individual skills, you need to let go of the four C’s—the desire to be competent, consistent, comfortable and confident. In order to foster teamwork, you can use the technique of saying “yes and…” rather than “yes but…” as a way of setting up the next person for success. Dr. Vera also emphasized the need of tolerance for error that allows for competent mistakes. By asking others to give you all of the arguments, you invite people to try it together.

Dr. Vera then introduced another framework starting with individuals to think about how to become an effective leader. Four types of competencies are under consideration: people competencies, organization competencies, business competencies, and strategic competencies. In terms of people competencies, improvisation develops listening and communication skills and teaches you how to be present. Organization competencies ask us how to create a culture of trust, learning, and experimentation, structure and systems that support real-time communication, decision-making and action. Business competencies look at building strong fundamental skills of character that includes values, virtues, and traits. Improvisation teaches you humility, teamwork quality, commitment (which includes aspiration, engagement, and sacrifice,) and learning to become vulnerable.

Action steps from improvisation:

– Begin with yourself: Know when your environment will accept innovation and improvisation; build skills, character, and attitude to improvise (fast response time); develop a safety net.

– Extend to your team: Practice “yes and…”;

– Support a climate of trust

– Do an organization audit: Ask—“do you look like the traditional theater or improv?” “what do you need to look like?”