Marc Lavine shared some of the ideas regarding the Competing Values Framework (CVF) and how it can help us become better paradoxical leadears.

Marc Lavine shared some of the ideas regarding the Competing Values Framework (CVF) and how it can help us become better paradoxical leadears.

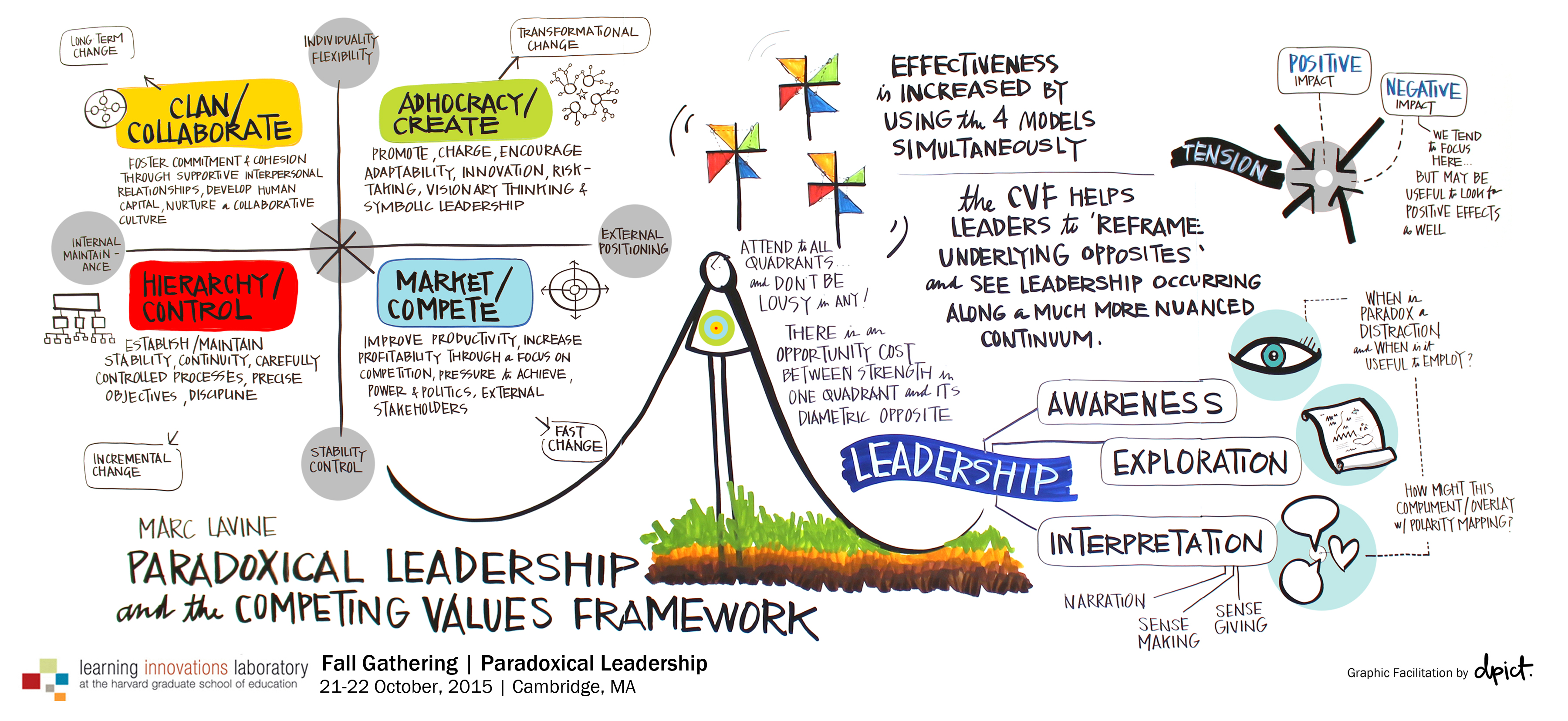

The CVF makes visible a certain set of paradoxes. I hope you find the CVF useful; it was created by University of Michigan scholars Kim Cameron and Bob Quinn. You can view it as a tool or resource to use in your organization; that’s great. Or you can think more in general terms; this is one way that might inspire you to think of other ways. Or you can think of it as possibly the source of useful interventions for leadership development. Marc addresses the relationship between leadership and paradox and explores the utility of the Competing Values Framework as a means to develop leadership skill from a paradox perspective.

The Competing Values Framework can support the development of a more paradoxical view of leadership that encourages greater leader behavioral and cognitive complexity as well as increased leader flexibility. Let’s sneak up on a broad topic like paradox by looking at a single set of specifics, one way of concretizing some of it. There is work by others that points at organizational benefits that accrue from greater ability to deal with paradox: such as responding with greater creativity, enhancing complex thinking, and enabling people to see more complementary possibilities between opposing sources of tension.

Developing leadership skills often involves paradoxical tensions. People need to deal with ambiguity, complexity and paradox.

The CVF is a tool that was developed through theoretical work, and then empirical testing. There is an instrument and assessment related to it. Ok, there is a two-by-two matrix—maybe that seems too simplistic. But I think it hits the sweet spot – just simple and complex enough.

There is tension at the diagonals. Example 1: organizations that focus on commitment and cohesion may neglect market forces, and vice-versa. Example 2: organizations that focus on stability and process may not be good at adaptation and innovation, and vice-versa.

The idea is that these are aspects of organizational life that are in tension. And organizations sometimes focus on one way of being vs. another. This means they have different primary paradoxes:

The model also has another level of complexity that might be valuable, if you want to read more on your own. There are four types of change, for example, and a type of leader that is characteristic of each quadrant.

Some arguments:

- The more quadrants an organization attends to, the higher effectiveness of the organization.

- It’s uncommon for an organization to be able to attend to multiple quadrants with excellence. It’s hard to be best at more than one.

- So a good strategy is to be excellent at one or maybe two, but then attend to the others.

- You may not be able to be terrific at each of these, but you shouldn’t be lousy at any of them.

- If an organization says, “success for us is about innovation and creativity,” that’s sensible (it’s the upper right), but don’t neglect the lower left quadrant, because you will lose a potential area of advantage.

Question: it seems to me that an organization might see these 4 types in different parts of the organization. So you end up trying to centralize and de-centralize at the same time, for example. Do you just shift from one quadrant to another?

Answer: I think about work on organizational culture; culture is not always consistent across the organization; there are sub-cultures. So by task or role there may be a focus on a different quadrant – a division that focuses on “control” in a “create” company. There is a book called Diagnosing and changing organizational culture that has an assessment, which can help suss out those sub-cultures. By using the assessment, you can locate your organization in the four quadrants, both in terms of your current state and your desired state.

Organizations change over time. For example, an entrepreneurial firm starts out focusing on creativity, innovation, etc. But as they grow, they begin to understand market forces better and begin to attend to internal HR issues. As they grow even more (C), they might even flip – a big play to create systems and structures to deal with that greater complexity. Finally (D) they may return back to the original focus as they realize they lost “what made us” – the original creativity and innovation – but hopefully with more balance.

Core logic of competing values: Both individuals and organizations need to operate adequately in paradoxically opposing–both/and–ways (team focused & market focused, agile & systematic) and amazingly in some quadrants to achieve true excellence. There is often an “opportunity cost” between strength in one quadrant and its diametric opposite.

Question: how do you know there is an opportunity cost?

Answer: In our research, we’ve rarely seen organizations that are strong in diagonally opposed quadrants at the same time. And if you track them over time, then you see as they grow in strength at the opposite quadrant, they weaken in the opposite.

Question: What causes organizations to shift from quadrant to quadrant? Is it the leader pushing or the organization pulling?

Answer: I don’t really know. My sense is that both are inputs. There is the influence of the leader for sure, but all members and all stakeholders also have an input, plus market forces. Which has more power, I don’t think we know. It probably depends.

Key insights

- The CVF encourages greater cognitive and behavioral complexity.

- Awareness of need to shift between, account for, and factor in various quadrants.

- The CVF heightens awareness of dynamic tensions within key managerial and leadership skills

- Even if I’m strong in one area, I don’t want to be so strong that I neglect all the other quadrants. Even if that means sometimes I have to do things that almost seem opposing at the same time.

- Paradox is made more manageable through the CVF

- Helps people see polarities as part of a continuum with greater nuance.

Key tasks of leaders: Awareness, exploration and interpretation of paradox. First being aware that paradoxes exist. Identify them actively. Then exploring the paradox, recognizing that there is an expansive range of possibilities, approaches, and stances (not getting stuck in either/or). Finally, interpreting the range of possibilities through sense-making, narration, or sense-giving. Providing followers an understanding of the both/and vision, while creating a culture of safety / avoiding cynicism.

Questions and Answers after the presentation.

Question: How much does the workforce need to understand? Especially if paradox exists in multiple planes, and not everyone is on that plane?

Answer: I view that as attending to paradox and taking action vs. sense-making and story-telling. I think it depends, on context and company values. For the case study I’ll share tomorrow, sharing the story was really important – it was important to highlight that this may feel kind of crazy or contradictory. But sometimes it can just seem abstract or unnecessary. Maybe specific examples are more appropriate then.

Question: Is there anything about how people have preferences for certain quadrants?

Answer: I’m a little suspicious of tools that work for individuals, teams, and organizations, but there is some work that supports that. You could fill out the assessment just thinking of yourself as an individual. But certainly in an informal way, people see themselves in certain quadrants. Overall, tensions are often thought of as a negative. But tensions can be very positive; sources of strength and advantage if leveraged.

Add a comment