Summary of LILA Member Call with Pat Satterstrom: The Power of Cultivating Ideas and Voice

January 2022

Notes by Hoa Pham

Introduction

On January 13th, LILA members joined the first Member Call of 2022 for a discussion on the role of voice, which can be considered a bridge between agency and belonging, two of the cornerstone topics (Oct. and Feb.) in LILA’s 2021-2022 theme “The Human Factor”. The call featured guest speaker Patricia Satterstrom from New York University.

About guest speaker

Patricia Satterstrom is an Assistant Professor at New York University – Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. She is also an affiliate of NYU Stern School of Business. She studies how teams can give voice to the voiceless, enabling team members to collaborate despite the power differences arising from professional and demographic boundaries.

Summary of presentation

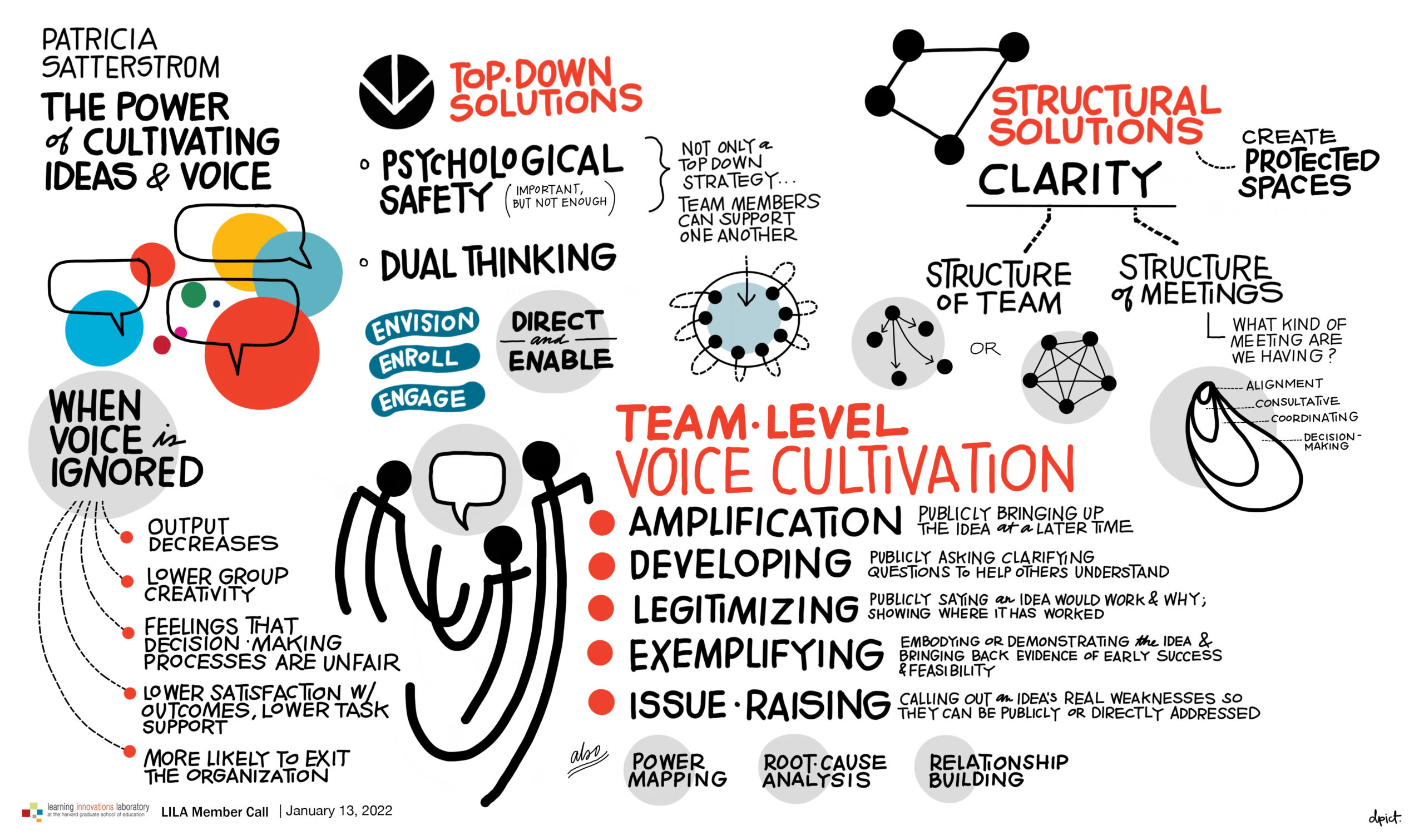

In many cases, teams are composed of people who come from different functional, demographic, or cognitive backgrounds. These types of teams provide great opportunities to study power, hierarchy, and voice, particularly voice of groups and individuals that may be overlooked. So what happens when people’s voices are ignored and what are the solutions.

The problem

Given the important role of voice in any organization, ignoring it can create both financial and motivational problems. Research has shown that when people’s voice is not heard, it is more likely that:

- Their output decreased 41% compared to when it was acted upon

- Groups demonstrate lower creativity compared to groups with higher levels of voice

- Those ignored found the decision-making processes less fair, were less satisfied with the outcome, and reported lower task commitment

- These employees gradually disengage and exit the organization.

Top-down Solutions

Patricia mentioned two top-down solutions: creating psychological safety and dual-thinking during crisis.

First, creating psychological safety is a proactive top-down solution which involves creating the conditions under which people can speak up. Five ways to do this are:

- Make it an explicit priority

- Facilitate everyone speaking up

- Establish norms for how failure is handled

- Create space for new ideas (even wild ones)

- Embrace productive conflicts.

Second, dual-thinking during a crisis is another top-down solution which requires holding competing ideas in your mind and having competing behaviors during moments of crisis. This involves the ability to:

- Envision possible problems but balance that with hope at the same time in order to have a realistic assessment of the situation while preventing people from getting overwhelmed.

- Enroll the “right” people on the team but also reach out to collaborate with diverse experts.

- Engage people by leading disciplined, coordinated execution while at the same time inviting innovation and allowing experimentation or failure.

Structural solutions

Having clarity about the structure in which they work has a huge impact on people’s ability to feel comfortable in the relationships that they have, which is a fundamental piece to being able to raise their voices.

A type of structure that can be helpful in creating a space for people to raise their voices is a meeting structured so that people have the chance for alignment (sharing information), consultation (soliciting information from other people), co-ordination (seeing what to do together), and decision-making.

Voice Cultivation Opportunities

Patricia also shared data and findings from a research project she has been conducting on voice cultivation opportunities.

It is common to acknowledge the role of managers and leaders in creating top-down spaces for voice. It is also known that sometimes employees do speak up and have the chance to offer constructive ideas for improving organizational or unit functioning to their leaders. However, these employees are not always listened to and their ideas are more likely to be ignored or rejected.

It becomes clear that much of the interaction in organizations doesn’t happen just between managers and employees but between teammates who have a role to play in upholding these ideas, pushing them forward and making sure that they reach implementation. This idea prompted Patricia to conduct her research to investigate the question: “How do team members help keep voiced ideas alive to reach implementation and make change?”

After almost two years attending weekly multidisciplinary team meetings in healthcare clinics for over two years and then recording, coding and analyzing the transcripts of these meetings, Patricia came up with the following findings:

- Team members, both lower- and higher-power, keep some ideas alive after initial resistance (~24%)

- From idea to change takes time (avg 41–74 weeks).

- Initial voicer of idea may no longer be around to see idea implemented.

- Idea can benefit team / organization at the expense of voicer.

She also presented a set of cultivation practices that team members can engage in to keep ideas alive. These include:

- Amplifying: publicly bringing up the idea at a later time.

- Developing: publicly asking clarifying questions to help others understand the idea.

- Legitimizing: publicly saying an idea would work and why; showing that a peer or competitor successfully used this idea.

- Exemplifying: embodying or demonstrating the idea and bringing back evidence of early success and feasibility.

- Issue-raising: calling out an idea’s real weaknesses so that they can be publicly and directly addressed.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Q: How can we enlarge the pie, meaning that you want people to have voice- not on your terms, but to have voice on their terms as well?

A: This is what makes this work a little tricky. No one would say that they are not an inclusive leader, but what we say and want and what we do are quite different. That delta is a place where this type of work can come in, because these are, in some ways, accountability structures. If you allow people to support each other, then you’re creating opportunities for ideas and for problems to come to the surface.

Q: How can we bring the self-awareness to leaders about their ability and effectiveness to seek and listen to voice?

A: A professor at Harvard Business School has done amazing work on showing that experts are really bad at working and teaching novices. Despite best intentions, we forget what it’s like to be new. So you create mechanisms, where you build trust with certain employees who might be able to say something. Some voices were quieter, so let’s think about starting with them next time, and I think that’s where the self-reflection comes in because you can’t build self-awareness unless you know it’s a problem.

Q: Have you looked at ideas competitions such as hackathons, and how do empowered people feel during that, and then afterwards are there lingering effects of impairment or disempowerment?

A: That can be an intervention for shaking up the status quo, giving these short bursts, where people feel like they can be heard in the different process. A lot of these hackathons, a lot of these incubators can serve as kind of moments to shake up the status quo for the individuals involved because they’re so highly curated. People are so thoughtful with removing titles, with creating open spaces for conversation, for having transparent decision-making processes, about which ideas are eliminated, which are included, which are brought together. And because of that, they create these spaces where people are more likely to speak up. The problem, though, is what happens afterwards, when people go back into the organization and go back into the status quo, because then they know what is possible and they’re not seeing it here.

Q: Was there something more generalizable from your research about the culture of the organization, or something of that nature?

A: First, the settings of the research allow generalizability because people in the researched context talked about psychological safety in the first meeting and then reality hit them. Like many of us, they have time pressure, they have a lot of constraints that impeded how they use different people’s voices. Second, while some of our work is large data survey work while some other work is qualitative inductive, which gives us a very deep understanding of the phenomenon. Therefore, while the former can help us confirm that this works for many people, the latter helps us see why and how these things happen. When people have spoken up on our behalf or amplified our voices, they’ve made a difference in how our ideas are carried out. Maybe I think that was a little bit of a longer explanation, but hopefully that will suggest that there is some generalizable findings.

Q: How does voice work when there is need for a transformational change?

A: That might be very different for mid-level managers, senior managers, and leaders who are at the top of the organization. For those who are near the top, one thing they should do is to think about structural things such as independent funding structures, resources that do not rely on the status quo. Also, it is important to have strong norms of confidentiality around the work that’s being done while also being able to be very transparent about the processes and share updates and minutes and contact product. Furthermore, create a culture within these kind of transformational spaces and build coalition, even if it’s at a more senior level, and that invites voices that are often not heard.

Q: With the techniques that you mentioned, what have you seen in terms of ideas that are dismissed not because of the quality of the idea but because of the origin or the source of the idea?

A: In some cases people’s voice is not heard simply because of the source and so a lot of that work is actually about how you build relationships across different lines. In some settings, focusing on the ideas is actually not a good place to start. Focusing on the relationships and legitimacy between the different types of roles is a much more useful way to start.

Q: Some leaders might shut down voices in some ways but still truly have the belief that they’re creating space for these voices to be heard. So what are some of the ways that you’ve seen that are successful in really creating a space that encourages people to raise their voices?

A: There are several things we can do about this. One thing is to look for some red flags such people’s refusal to raise their voice despite the leader’s repeated encouragement. Another thing to do is to have someone observe and see if the room feels different.