Dr. Wendy Wood, Provost Professor of Psychology and Business at the University of Southern California, presented the event’s first provocation by sharing her research on habits. In the talk, she explained what habits are, how they can become misaligned with our intentions, how they are often the default response (winning out over other behaviors), and how they often are useful.

She opened by sharing her research on the habit of eating popcorn at the movies. We usually think we’re eating because we want to, like to, or somehow it meets our needs. But this isn’t always the case—eating might be a habit, where you respond out of a habitual pattern and not necessarily because you want to, or like the taste of the popcorn. In fact, people with a strong “movie popcorn habit” will eat even stale popcorn. The outcome (enjoying tasty popcorn) is no longer what drives the behavior; instead the setting and context cues drive the behavior. This is the definition of habits—behaviors repeated to the point where the outcome is no longer important; they are cued by the context instead.

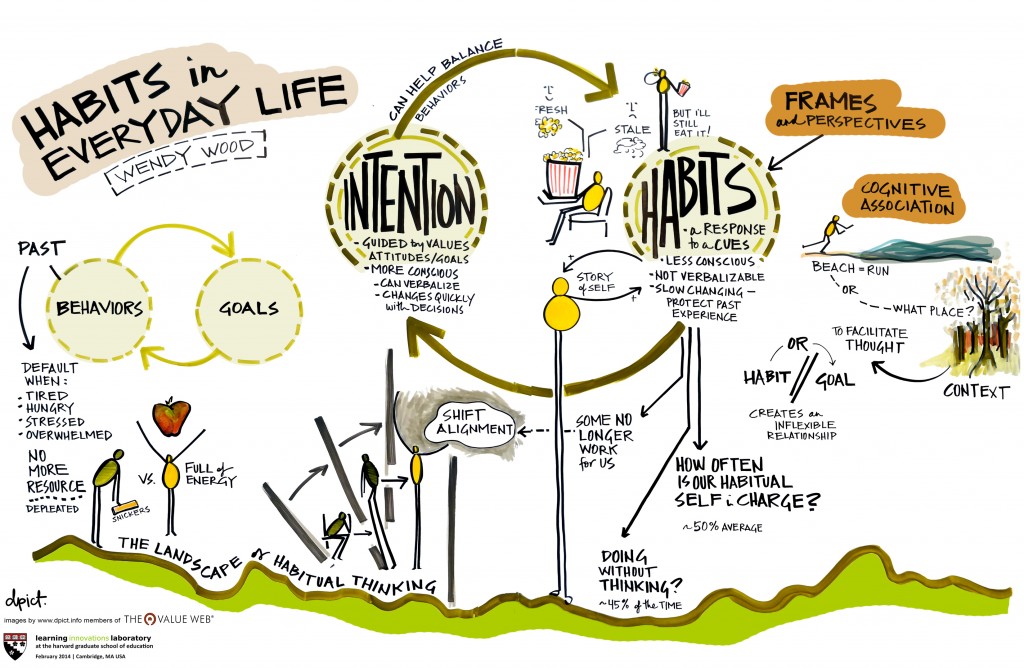

Wood shared the “two selves problems”—that we all seem to have two selves, one intentional and one habitual. The intentional self is guided by attitudes, goals, and values. It feels more conscious and changes quickly via decisions. The automatic self is not necessarily conscious; we don’t always know what our habits are and can’t always label them or verbalize what we are doing. The habitual self changes slowly via experience / repetition. That’s a good thing—you don’t wipe out everything you have learned before when you learn something new; this protects past experience.

Contexts drive habits. If you have a habit of running on the beach, if you see the beach, you should think about running. The thought of running is accessible and drives performance. Habit performance stems from what is currently accessible in the mind. Wood and colleagues testing this using word association / priming. They presented those places where people typically ran to people and then did word recognition for “running,” “jogging,” etc. People were more quickly able to recognize those words when presented with contexts, but not their running goals.

How often is the habitual self in charge? Wood and colleagues did a self-report study with an hourly beeper to find out how often people do things daily in the same place. 50% of actions were repeated in the same contexts everyday—for work days alone, even higher. 45% of actions were done while thinking of something else. This means that much of what we do each day can become habits.

But people underestimate the role of the habitual self. It feels like we are acting intentionally when habits are consistent with goals. We make up stories to make our habits seem coherent and logical. That’s functional, because it allows us to experience the self as cohesive.

However, many of our behaviors are both habitual and intentional. Many complex behaviors require both components. We are very good at integrating these multiple brain systems; but it’s helpful to recognize that there are multiple brain systems at play.

Habits often work for us; they help us function in complex environments. Habits are the default response, when we don’t have energy or ability to be intentional. They are automatic, easy, efficient, and fast—but not necessarily aligned with the intentional self. In other words, habits are helpful, but they don’t always stay helpful. We struggle with our bad habits, those that aren’t really working for us anymore.

Good habits and bad habits function very similarly; the difference between them is the alignment with goals. Wood and colleagues did studies with college students, asking them to choose snacks after an effortful activity (so their willpower/motivation was low). When people don’t have time to deliberate, are tired, or have low willpower, they fall back on their habits. Students with a strong healthy snack habit chose a healthy snack even when depleted. So healthy habits can counteract the negative effects of willpower depletion.

The habitual self doesn’t follow intentions, but takes guidance from past behavior. Most of the time habits are aligned with intentions, which is fortunate, because life is draining and we need something to fall back on. Habits can ensure we meet our goals when our intentional self falls short.

Day 2: Habits in the Workplace

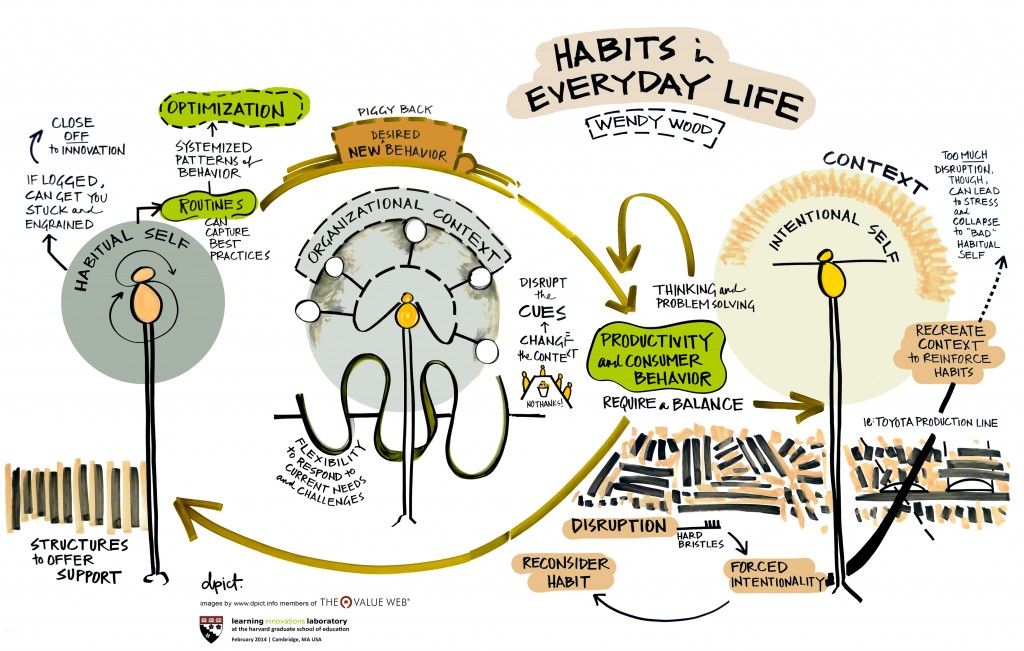

Wendy Wood offered the second provocation on the second day. She talked about habits and inertia in workplace and consumer behavior. Both habits and intentions / problem solving contribute to workplace productivity. She discussed optimizing habits through separation, disruption, and leverage.

Wendy Wood offered the second provocation on the second day. She talked about habits and inertia in workplace and consumer behavior. Both habits and intentions / problem solving contribute to workplace productivity. She discussed optimizing habits through separation, disruption, and leverage.

We often imagine habits and routines on one end of the productivity continuum, and critical thinking, problem solving, and acting intentionally at the opposite end. But Wood doesn’t think that. She thinks that habits and routines can also lead to productivity. There are good habits and bad habits and good decisions and bad decisions.

She cites a Paul Adler paper on the role of habits and decision-making in organizations.

Productivity depends on both efficient, best practices (which may be habits) plus innovation. Some things need to be proceduralized; others require innovation and problem solving (e.g. to keep up with the marketplace, with changing technology, competitors, etc).

How can we optimize the balance between habits and innovation? As organizations mature, exploitation of efficiency can trump novel exploration. For example, the automobile industry (Abernathy 1978 and Adler 2009) has tended to focus on developing effective routines and then end up stuck in the past. The marketplace changes and they are not able to adapt and innovate. Focusing on past practices has led to less optimal performances, as it inhibits ability to adapt.

With maturity, even close relationships become habitual and not intentional (Simmons 2010). Wood investigated 79 dating individuals, reporting their behavior for 2 weeks. Some were together less than a year, 1.6 years, and almost 3 years. They were asked, how much do you intend to support your partner the next day? Then the next evening, they rated how much support was actually provided. People had low, average, or high support intentions. The people that had been together the longest had the flattest line; intention doesn’t matter for how much support they give. The shortest relationships had the steepest slope, meaning they actually did give more support when they intended to.

What to do? How can we handle the tension between developing habits based on past experiences and being more flexible to meet current challenges? Wood offered a personal example of the separation strategy. She is vice-dean for social sciences. There is also a vice dean for humanities and natural sciences. They are supposed to figure out direction and scientific vision. The vice dean for policy keeps everything on track. All 4 report to the dean. So in that way, we have 3 people pushing for innovation and one person pushing for habits. The dean makes it clear that best practices are something that have to be listened to, and also that the vision the academic deans have is to be supported. In this way, the focus on innovation is separated from the focus on habits.

But this tactic may depend on a strong dean keeping the connection.

The second way to optimize the 2 forces is to disrupt individual behavior. Disrupting the environment gives people a window of opportunity to act on intentions rather than habits. Lee (2013) created terrible toothbrushes, which were super short and hard to hold or had weird bristles. How do people experience using them? People reported thinking much more about their dental health during these 2 weeks. As they tried to figure out how to cope in this new environment, they developed new ways to brush to meet their goals.

Disruptions can also be simple or small but still have significant effects. Wood instructed people to eat popcorn with their non-dominant hand to disrupt the habitual action sequence, and offered both fresh and stale popcorn. When using their non-dominant hand, nobody ate the stale popcorn, even those with strong popcorn eating habits. This disruption made it difficult to go on autopilot—to be guided intuitively by action cues. It put the intentional self back in charge.

Toyota also uses disruptions, novel stimuli to disrupt execution of specialized routines (Brunner, Staats, Tushman, & Upton, 2011). For example, they might speed up or slow down the production lines to disrupt habits. They have a “JIDOKA” process that stops production automatically when problems occur, allowing them to bring intentional scrutiny to what has occurred. This brings habits in line with intentions.

You can also change the context and the cues, which will nullifies habits. For example, Wood asked students to eat popcorn in a darkened conference room, while watching music videos. Since this wasn’t a movie theater, the popcorn eating habit is not activated. Everyone (strong “movie popcorn” habit or not) ate more fresh than stale popcorn.

When people move house, they act more aligned with their environmental values (Verplanken, Walker, Davis, & Jurasek, 2008), since moving disrupts their habits and allows them to act more in alignment with their intentions. Wood studied transfer students. They kept their exercise habits if they had the same context available. E.g. If there was a gym in their dorm at their old university and at their new university, they kept the habit. If not, they lost the habit unless they had a strong intention.

Disrupting contexts can get people to act more intentionally, and be more responsive. But you also risk losing some positive habits that may have been working in the past, if they were habits without strong intentions.

The third tactic is leveraging habits to promote desired performance. Habits can impede selecting, acquiring, and using new products (Ram & Sheth, 1989; “innovation resistance”). Why? Product slips (much like action slips, Reason, 1979): when consumers intend to use new products, they don’t. Competing habits are performed especially when preoccupied, or not thinking about what one is doing.

Wood and colleagues did research with Proctor and Gamble, investigating how to overcome people’s habits for old products. They did an online survey, where consumers nominated a product they had purchased, intending to use, but didn’t. Why? 25% were thwarted by product slips. They fell back into doing what used to do, before purchase. These slips occurred despite consumers’ favorable intentions.

Wood and colleagues also did an experimental study of new laundry product, a fabric deodorizer. The deodorizer is an alternative to existing laundry habits: doing laundry or re-wearing smelly clothes. They monitored product use for 4 weeks and tried to convince the students to use the new product whenever they thought of doing the old habit (either laundry or re-wearing). They were able to piggy-back the desired behavior onto the current behavior, which is leveraging the old habit to support a new one.