“A Deeper Dive Into DDOs”

The Deliberately Developmental Organization (DDO): How Organizations and their People Can Help Each Other Flourish by Robert Kegan

Dr. Kegan began his session by posing the following provocation: What are the structures we have created as a society to support the ongoing development of people after they graduate from schooling or finish their last degrees? Given the inordinate amounts of time people spend at work over the course of their lives, Dr. Kegan and his colleagues began investigating the types of deliberate practices that workplaces, as important delivery systems of ongoing learning, have the potential to use to enhance and support adult development in the workplace and beyond. “Next to our love, the most precious thing we can give to another is our labor,” said Dr. Kegan, “so we should ask, “What do I want in return?”

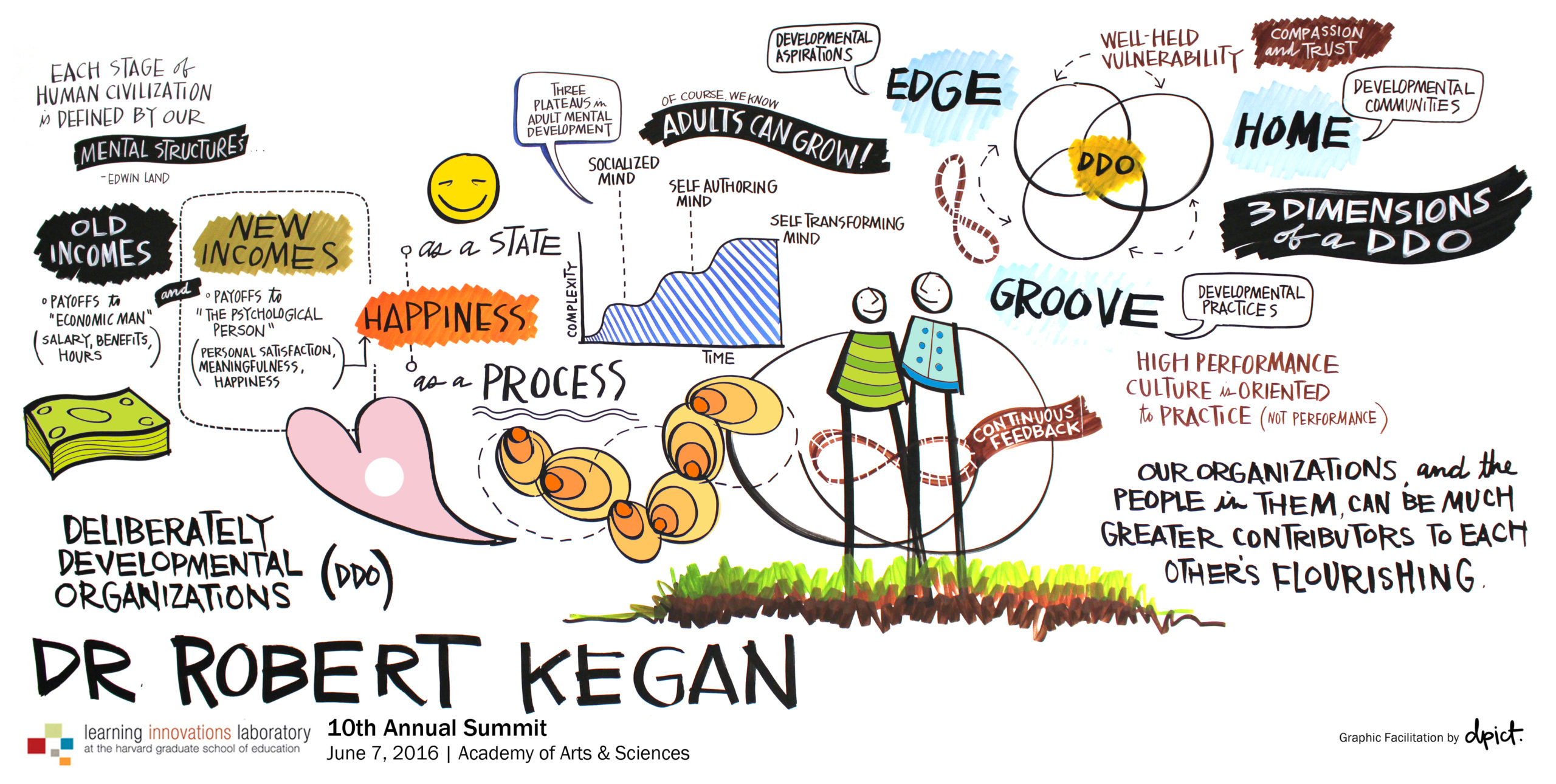

To answer this question requires a fundamental restructuring of the work-reward relationship that has prevailed throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. During this period, payoffs and incentives were given to the “Economic Man,” dubbed by Dr. Kegan as the “old incomes:” e.g. salary, benefits, hours and other material supplies to support the external life. Alternatively, the 21st century requires payoffs to the “Psychological person,” or “new incomes,” such as personal satisfaction and happiness. Here, Dr. Kegan draws a clear distinction between two potential streams of human happiness, both derived from classical schools of thought: happiness as a state (i.e. vitality, exuberance, buzz, banishing of pain and suffering; hedonism in its classical sense) and happiness as a process (i.e. personal flourishing, transforming into a better version of oneself, growth, development; Aristotle’s notion of Eudaimonia). According to Dr. Kegan, an example of an organization that pursues happiness as a state of being could be any start-up that prioritizes a myriad of perks for its employees, while an example of an organization that pursues happiness as a process of being would be the DDO—the deliberately-developmental organization.

Adults Can Grow

Kegan’s Constructive-Developmental Theory, known as CDT, posits that our individual mental structures have the potential to become more complex over time. CDT in particular was watershed in psychological literature because it provided a framework for how development continues well past the end of adolescence into the ends of our lives (for further reading, see LILA archived summaries for Dr. Kegan’s In Over Our Heads and Immunity to Change). Just as medicine was transformed by incorporating advances in the science of infection, Dr. Kegan suggest that, in a certain way, we have a robust science of adult development that we are not sufficiently harnessing or applying to our approach to work.

The DDO

Dr. Kegan’s study of organizations yielded four cases of companies that modeled the unique properties of a deliberately developmental organization. In the words of one of these organizations (Decurion Corporation), “Flourishing is the process of living into one’s unique contributions. It is the process of becoming oneself. We expect to do this through our work.” In the words of another, Next Jump: “Caring for your employees and helping them grow as human beings is possible while making money and helping the world become a better place.” Dr. Kegan underscored that each of the organizations featured as DDOs in his book were selected from a pool of hundreds of organizations that his team studied, and that each DDO was not only from a different industry or market, but was also financially high-performing. Thus, the common criticism that a developmentally-oriented organization may lead to “happiness as a process” but also lead to lower bottom-line performance is not supported by Dr. Kegan’s research.

Instead, the DDO emerges at the intersection of developmental aspirations, developmental communities, developmental practices.

Most organizations are not built to support ongoing development. In most organizations, employees and leaders alike expend precious time, effort, and resources on an unpaid “second job:” hiding their weaknesses and managing others’ favorable impressions of themselves by creating layers and forms of self-protection. This “second job” exacts a cost on the person by inhibiting her/his growth and thus, on the organization as a whole. The DDO eliminates this “second job” altogether by deliberately upholding the values of transparency and vulnerability for all members and at all levels of the organization.

Well-Held Vulnerability

Thus, vulnerability is a core tenet of the DDO, specifically manifesting as what Dr. Kegan calls “well-held vulnerability.” In a DDO, not only are you, as an employee or leader, invited to be your best; you are also invited to manifest your weaknesses on a regular basis as a means of recognizing that your weaknesses, in addition to your strengths, are sources of your own potential becoming. The DDO, in essence, takes an entrepreneurial approach towards its entire people development model. Feedback and an iterative, growth-mindset orientation is continuously employed within a DDO, and the role of coaching becomes a key mechanism for driving ongoing personal and professional development for organizational members. “Well-held vulnerability” is distinct from vulnerability in general in that the organization creates scaffolding and spaces that support its employees in their acts of vulnerability through safety and deep human compassion.

But how does one create and sustain a DDO? You need a groove, says Dr. Kegan. Unless your organization has practices that are baked into its DNA, which are also reinforced at all levels of the organization on a consistent basis, it is difficult to create a DDO that truly lives up to the name. Examples of some practices that have been employed by the DDOs featured in An Everyone Culture are:

- A company-wide practice where employees and leaders publicly identify whether they lean insecure or arrogant

- Bonuses are given based on 50% of revenue generation and 50% of culture contribution

- In any meeting with three or more people, everyone has an iPad survey that they use evaluate everyone else in the meeting on different dimensions

- Every month, in front of the entire company, select members of the organization present their contribution to the company and are given feedback

Building Adaptive Capabilities

In addition to the old and new “incomes” discussed above as a marker of a shift in the work- reward dynamic between the 20th and 21st centuries, there is also a much-needed shift in how development itself is done in the workplace. The 20th century answer to how to develop people focused on executive coaching, high-potential programs, leadership development programs, mentoring, corporate universities. The challenges of this type of approach, however, include the following:

- Too punctuated – Sessions are not often or intense enough

- Something “extra” – There is a problem of transfer from the training room into practice

- For a few – Why write off the potential of 95% of employees by only selecting a small group to be further developed?

The DDO provides a 21st century-appropriate method of building adaptive capabilities of the people within organizations by baking a developmental approach into all aspects of its operations.

Traditional Organization vs. the DDO

During the Q&A portion of Dr. Kegan’s session, several questions were asked about the potential pitfalls of the DDO. For instance, how does a DDO protect against the abuse of power and using “well-held vulnerability” as a method of control? Do all members of an organization experience equal pressure to be vulnerable? How does a DDO deal with unconscious bias as opposed to an ordinary organization? How applicable is the development that one has/experiences in a DDO if they leave the DDO and move into a non-DDO? Does or would ittranslate?

While Dr. Kegan was only able to speak to the way the DDOs in his sample set grappled with these questions, he also reminded us that while we rightfully assess the costs and benefits of the DDO, that we are mindful to also assess the costs of the “traditional” or “ordinary” organizations within which we operate today. It is unclear, at this stage, whether the DDO is simply a fluke or a strange, ineffective experiment in the long-term or whether it is a harbinger of how organizations will be oriented in the future for better results.

A Paradox

Finally, Dr. Kegan outlined a key paradox that stands in the way of our building DDOs that are also high-performing: a truly “high performance” culture does not emerge within companies that hold orientations toward performance; they instead emerge when organizations are oriented towards practice. In other words, if one looks at work in terms of performance alone, then the thought of ongoing feedback is threatening, and reinforces the existence of the “second job.” Instead, at a DDO, everyone works with a practice orientation—looking continually towards the opportunity to get better at things—which naturally lends itself towards higher performance. As one of the members of a DDO stated to Dr. Kegan and his team: “I’ve had more painful and uncomfortable experiences in this setting and I would never want to work anywhere else.”

Add a comment