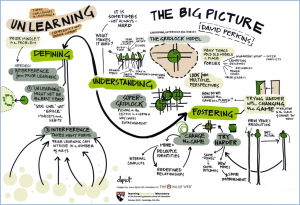

David Perkins shared some of his thinking about some of the challenges of unlearning. There are many ways to dig into the topic so he invited us to consider what is the big picture about this year’s theme in three ways:

Defining Unlearning: Broadly speaking we can think of it as interfering with prior learning. Lots of learning builds on prior knowledge and beliefs. But there are other situations in which prior habits, mindsets, or systems are obstacles. A second point is that unlearning may not be the best term because you don’t really erase something, you typically bracket or sideline habits or mindsets. However, what is unlearned is always lurking and can easily pop back up, particularly in stressful settings. Lastly, the interference is not one thing. It takes many forms. Mindsets, habits, and systems can combine to make complex interference. Katie’s brief names a host of ways that these areas can become obstacles. Rather than say we should discount the term unlearning, we should embrace that there are lots of facets with similarities and differences (just like lots of other terms we use, including learning).

Understanding Unlearning: Perhaps the big thing to understand here is what makes unlearning, in it’s complexity, hard. Can we make big generalizations? Dave thinks we can. Firstly, unlearning is not always hard. There are many cases it is relatively easy with intention and practice (such as language learning). But when it’s difficult what is going on? Dave suggests a model, the gridlock model — multiple, conspiring interlocking influences that create a sense of stuckness. They hold the habit, mindset or system in place and we should look for the gridlock. Sometimes there is even, “super-gridlock” — when you push on the gridlock it gets even stronger.

Fostering Unlearning: Given all this what can one do? We have been exploring an impressive array of tips but can we say something about the general way forward? Dave suggests there is a difference between “trying harder” and “changing the game”. He reminded us of research that suggests that almost 0% of people actually sustain their New Year’s resolutions. Trying harder can take the form of trying again or mustering more energy or attention to do something or thinking differently. But often then don’t help because they bump up against gridlock. The other approach is to change the game — reframing the problem and attempting new sorts of approaches that don’t just push the current habit or mindset. It’s like finding or building a new door rather than push on the wall.

Marga Biller

Could we take an approach similar to the 3 stances when approaching unlearning? That is to say, if we asked ourselves what needs to be unlearned before we start to learn something, would we have a better chance of making progress?