December 2017 LILA member call: Authority or Community? A Relational Models Approach to Understanding Leadership Emergence

Listen to the Member Call on Authority our Community: Leadership as it Emerges in Groups

Dr. Wellman, Assistant Professor of Management and Entrepreneurship at Arizona State University’s W.P. Carey School of Business joined the December 2017 member call and shared his research on the context that allows leaders to emerge at all levels of an organization. Below is a summary of the ideas that Dr. Wellman shared with the LILA Community.

Organizations need more leaders in more places

Dr. Wellman asserts that leaders are needed at all levels of the organization so people can “practice” leadership and create a pipeline of leaders He defined leadership in a behavioral context- a leader is someone who engages in social influence (figuring out a big picture goal for the group, motivating others to pursue objectives, establishing a positive climate) on behalf of the group. This definition suggests that everyone can be a leader—divorced from position of formal authority. Therefore, emergent leadership is when people who aren’t “supposed to lead” become empowered to lead by engaging in social influence behaviors.

But, accomplishing this is easier said than done

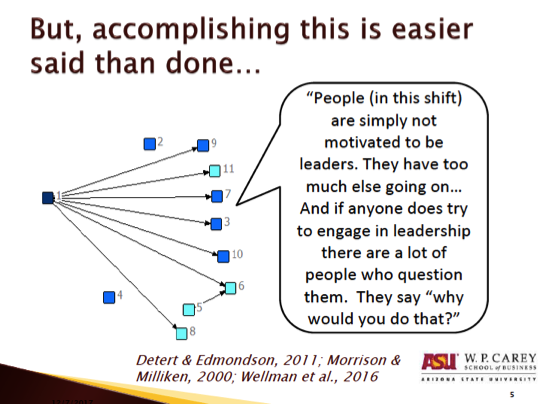

Powerful barriers and pressures that work against emergent leadership–people are scared to speak up, worried that they will be judged, seen as a nuisance, seen as going over boss’ head. Even in environments where people consciously assert that they want workers at all levels to feel free to give their insights, it can be difficult.

Dr. Wellman’s dissertation included studying leadership emergence in nursing shifts at hospitals that encouraged systems of emergent leadership (“patient-based care”). The hospitals want to encourage people at all levels to share insights on patient care; wanted to structure their leadership within nursing shifts so that everyone felt comfortable sharing insights. He developed a mapping system to visually represent the interactions amongst the people in the shifts. Despite the fact that hospitals were trying to be very emergent, he found that most maps of how leadership was structured in each shift were very hierarchical. When Dr. Wellman showed the results to nurses, he heard that often they aren’t motivated to be leaders, have other things going on and when they did try to engage in leadership it’s wasn’t always met with a positive response (sometimes people questioned them about why they were stepping up).

Dr. Wellman’s dissertation included studying leadership emergence in nursing shifts at hospitals that encouraged systems of emergent leadership (“patient-based care”). The hospitals want to encourage people at all levels to share insights on patient care; wanted to structure their leadership within nursing shifts so that everyone felt comfortable sharing insights. He developed a mapping system to visually represent the interactions amongst the people in the shifts. Despite the fact that hospitals were trying to be very emergent, he found that most maps of how leadership was structured in each shift were very hierarchical. When Dr. Wellman showed the results to nurses, he heard that often they aren’t motivated to be leaders, have other things going on and when they did try to engage in leadership it’s wasn’t always met with a positive response (sometimes people questioned them about why they were stepping up).

What determines leadership emergence?

The traditional way of thinking about this that there is something unusual about people who emerge as leaders (charisma, intelligence). However, current research finds that Big 5 personality traits explains only 23% of variance.

Leadership emergence as group development

Dr. Wellman presented amodel of group development that he has applied to leadership emergence:

- Sensemaking (script adoption): early on in a group developing, they try to interpret their environment to figure out what they should be doing. People adopt cognitive templates based on their observations

- Interacting: Individuals then interact using their own templates and through their interactions they influence one another and their templates become more similar.

- Cementing: In the life of a group, a shared consensus emerges about who the group is and how they organize their activities – becomes the norm, resistant to change.

- Challenging: Instances when people have the occasion to question their assumptions and potentially change them.

Relational Models Leadership Theory

Early on in the life of the group, signals from the context influence the relational template that members adopt about leadership—they go through the sensemaking process and they converge on a cognitive relational model for how leadership should unfold within the group. The model influences how they interact with people, which helps determine leadership emergence. This finding suggests that these models (and contextual factors that can help encourage one model or another) can influence leadership emergence.

Alternate scripts for leadership

Dr. Wellman used Allen Fiske’s anthropology research that asserted that all relationships and human interactions are governed by 1 of 4 potential templates for how people could interact—this suggests that leadership is also governed by these templates and can narrow the templates down to 2 that are relevant to leadership.

Dr. Wellman suggests that there are two relational templates that members of groups predominantly use in figuring out how leadership should be performed:

- Authority Ranking (AR) model: Hierarchical approach to figuring out who should lead; people look at others and decide who has the most valuable personal attributes and implicitly rank one another according to attributes–defer to the people who they perceive to be high ranking in leadership qualities. Leaders are responsible; lower ranking members are expected to support (example: military)

- Communal Sharing (CS) model: All members of the group are seen as equally valuable. Everyone has valuable relevant insights that can contribute to the group; leadership is more about consensus rather than deferring to authority (example: Zappos)

Relational Models Leadership Theory

Dr. Wellman’s theory asserts that a group adopts one of these two models for leadership (Authority Ranking or Communal Sharing) and that model drives how leadership unfolds within the group.

Perceived similarity and relational model convergence

What determines which model members of a group adopt?

Drawing on group development, Wellman asserts that the sensemaking stage is important in determining whether leadership is more authority-based or communal-based. A key difference in the two models is how much members in the group need to be attentive to differences between themselves.

- In Authority Ranking, you must be very attentive to differences between members so you can rank them into a hierarchy

- In Communal Sharing, you see everyone as a member of the same team and the focus is on the similarities between each member.

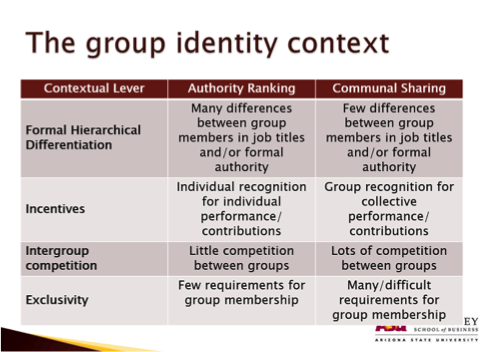

The group identity context

The pressures within an environment push people towards the Authority Ranking model or the Communal Sharing model. If you are interested in encouraging a particular model, Wellman suggests that there are some levers you can use to influence a group such as job titles (“formal hierarchical differentiation”), incentives, intergroup competition, and exclusivity

Personal attributes of emergent leaders

When a group adopts a certain model, it has important consequences for how leadership emerges within the group.

- Authority Ranking: leader emergence based on leader-prototypical attributes (intelligence, dedication, charisma, formal authority)

- Communal Sharing: leader emergence based on group-prototypical attributes (kindness, compassion, warmth, benevolence)

Behavioral style of emergent leaders

The model that a group adopts will influence the type of leaders that emerge and also influences how leaders behave (the “leadership style”).

- Authority Ranking groups defer to emergent leaders to set the agenda for the group and help the group fulfill the agenda; groups expect the leader to initiate structure and communicate vision

- In Communal Sharing groups emergent leaders expected to facilitate participative decision-making; groups expect the leader to be considerate and stimulate intellectual conversation.

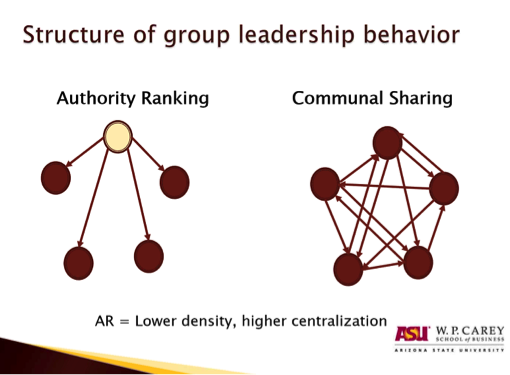

Structure of group leadership behavior

Over time, these models influence the way that leadership is structured in the group:

Lower density: in AR, there is less overall leadership behaviour.

Higher centralization: in AR, leadership behavior is likely to be concentrated in fewer people.

Relational Models Leadership Theory

As people see leadership being enacted that is consistent with one of these two models, it solidifies the model. Over time, the model become institutionalized–when people depart from the model they may receive push-back. Once there is an established pattern of leadership within a group, it is hard to change to a different pattern.

Identity and technical jolts

After enacted group leadership structures have stabilized, two types of events or jolts can cause them to shift:

- Identity jolt: something that causes people to see themselves as more similar or different than they assumed (e.g. negative performance feedback, conflict).

- Technical jolt: externally imposed change that causes people to change the way they do their work (e.g. process change, software implementation).

Takeaways

- Cognitive relational models drive leadership emergence.

- Cues from the organizational and intergroup context (like reward systems, job titles, intergroup competition, exclusivity) influence model adoption.

- Identity and technical jolts can be used strategically to promote desired patterns of emergent leadership.

Community Discussion

Q: When can these two models be most effective?

A: The AR model is preferred when people are working on stable, repetitive tasks like making widgets. For groups that are doing knowledge work, the CS model can potentially be more effective because it will encourage more people to engage and offer their perspective.

Q: Is it possible to have a hybrid model? We often see the role of leader can be to hold the communal frame, ensure the collaboration of everyone.

A: That’s an interesting potential next step; my initial work shows that it’s hard to coach people to lead in this way.

Q: When you talk about organizational cues, how does alignment between behavior and words influence these cues?

A: When there are conflicting signals, people revert back to their disposition and what makes sense for their task and then when people reflect back on this, a model will emerge.

Q: Are there gender differences in leadership styles?

A: I don’t have any specific findings at the organization level but my own research findings line up with your intuition that women tend to drift towards the communal template. Alice Egly has done studies that show that the template that society has in mind make it difficult for women to fulfill expectations for them and leaders.

Q: Is there an example of someone who are strong at shifting between these styles?

A: Maybe Bill Gates at Microsoft—a lot of their work is done on a shared platform but he is seen as a central authority figure.

Q: Have you seen practices in which having a more communal leadership model becomes more effective?

A: Communal leadership emphasizes that everyone is valuable and focuses on the similarities rather than the differences. Often there are times when one person monopolizes the conversation and they tend to emerge as a leader because people assume they since they talking the most, they are unusually qualified to lead. But sometimes that’s not true. Laying the groundwork early on about what the group’s interactions should be and potentially highlighting the qualifications that everyone in the group is bringing to the table can shift to a more communal form of leadership. Also having shared values and shared goals will help people focus on communal ways of engaging in leadership towards one another.

Add a comment