Introduction

As we think back to both the October gathering and last months’ member call with Spencer Harrison, we’ve been exploring what system leadership looks like and what the capabilities of system leaders are. One of the more important capabilities of system leaders involves creating what Mary Uhl-Bien called the ‘adaptive space’ – a space that facilitates both generating new ideas and the implementation piece of innovation, so that initiatives can take root at scale. Last month, Spencer provoked our thinking about the idea that productive curiosity can help us see the system, as well as create opportunities for innovation. Since then, we’ve been wondering: how can we organize our efforts to meet our organizations’ needs in the midst of change and uncertainty? As we’ve learned, the complex problems and systemic issues we’re trying to address require us to foster diverse ways of thinking.

These are some of the questions from past sessions that we’ll be revisiting:

- What can leaders do to effectively manage diverse teams?

- How can the needs of diverse teams differ, and what forms of leadership are best to address these needs?

- How might organizations pair leaders with teams to enhance performance?

- What are the leadership behaviors and skills that moderate the effects of team diversity?

Listen to LILA December 2020 Call

Overview

Leaders are in an ideal position to help teams – that are complex systems – to capitalize on the potential benefits of diversity, while mitigating its possible downsides. Leaders are uniquely capable of overseeing the whole team’s functioning and typically more influential to team processes and outcomes than any other member of the team. This presentation reviews how the differences between people affect their interactions in team settings. The definition of diversity in this case is very broad and includes both visible, demographic characteristics as well as more invisible characteristics, such as personality, values, and tenure. Diversity is a double-edged sword: It can lead to greater performance given heightened creativity and improved decision-making, but it can also instigate lower performance due to misunderstandings, distrust, and bias. These different dynamics in diverse teams create different needs that require substantially different types of leadership behaviors, implying that there exists no one-size-fits-all solution to leading diverse teams. Rather, leaders must differentially apply task- or relationship-focused behaviors in order to match the needs of diverse teams, which shift over time. For this, leaders need to possess or acquire certain skills that aid them to (1) understand what is to come, (2) be receptive to what is going on, and (3) show behavioral flexibility. While some leaders may be naturally talented to do this, others can develop these skills. For example, leaders can improve understanding through diversity training or by engaging in multicultural experiences, such as spending time as an expat. These multicultural experiences can also help improve leaders’ social receptivity. Leaders who possess interpersonal flexibility or have higher cultural intelligence have an advantage for behavioral flexibility. Importantly, both flexibility and cultural intelligence can be stimulated by multicultural experiences and encounters. Only those (future) leaders who develop a profound understanding of what diversity can elicit in teams, grow and exercise their social perceptiveness, and show high behavioral flexibility will be able to effectively lead in times of diversity.

Summary of presentation

Astrid started studying diversity in teams back in 2001 because she was intrigued with the idea that diversity could be a double-edged sword when it comes to team performance. For example, there are some instances where diversity can be really good for teams, and others where diversity in teams can lead to really negative effects. Her research has shown that there is not just one type of leadership that works across all diverse teams.

At first, Astrid investigated how certain structural factors influence the performance of diverse teams. For example, at an organizational level, what is the impact of reward structures on team outcomes as well as factors at the individual level, such as how individuals feel about diversity and how that impacts the way they worked with others in teams. That then led to a focus on leadership, as a way of understanding if and how leaders could shape how diversity influences team performance.

A systems approach to leading diversity

For her research, Astrid looked at leadership as a formal, supervisory position. The teams themselves may work on relatively complex tasks, but they are independent of the leader. And that distinct boundary – the boundary between team and leader – makes the leadership of diverse teams especially suited to a systems approach. After all, the teams themselves are complex and dynamic systems, and if you add diversity into the mix, they become even more complex. Prior to the study, it wasn’t clear how leadership influences the effects of team diversity.

Diversity Definition

People have a lot of ideas when they think about diversity. The definition of diversity that Astrid uses is fairly broad: Diversity denotes differences between individuals on any attribute that can lead to the perception that a person is different from the self. This implies that the definition not only includes ethnic, cultural and age differences, etc., but rather any differences that people may perceive in others. These differences also include invisible differences, such as a person’s personality, values, educational background, norms, etc.

Team Diversity: Double-Edged Sword

Research focused on team diversity indicates that team diversity can be double-edged sword. For example, in some instances team diversity can lead to negative team processes and outcomes. You may be familiar with concepts such as social self-identity theory, or self-categorization theory; ideas that underscore the fact that people tend to prefer to work with those who are similar to them. People tend to have a general bias against people who are not from their group. Note that these types of conflicts don’t only arise when there are racial differences but can also be caused by personality differences.

These sorts of tendencies and biases thus can instigate conflict, distrust and dislike between people from different backgrounds. And, to no one’s surprise, these negative team responses are then associated with negative team outcomes.

On the other hand, diversity in teams can also lead to positive effects. This angle is inspired by more of a business-minded perspective, which has traditionally posited that diverse teams are thought to be associated with good performance due to the fact that the team benefits from team members’ different perspectives, ideas, and approaches. Indeed, teams that can integrate a multitude of perspectives into their workflows by talking about them, exchanging them, processing them, and compiling them as a group tend to be higher performing.

Yet one interesting thing we’ve found is that the type of diversity does not matter – all types and combinations of diversity characteristics can be affiliated with either negative or positive team outcomes. It doesn’t matter whether the team is diverse in terms of visible or invisible characteristics. Rather, we found that what matters most is leadership – or specifically, leaders who can manage diversity well.

Leading Diversity

When Astrid first started her research journey, she and her colleagues were interested in seeing what the literature revealed about the leaders’ role in managing team diversity. They found 44 empirical papers that focused on the interaction between team diversity and leadership, but these papers used a variety of diversity characteristics, and also a variety of leadership styles, behaviors and characteristics. This huge range indicated that there wasn’t really a systematic approach to looking at how leadership matters for diverse teams. What’s more, their meta-analysis revealed that there were a number of inconsistencies in the literature; in some studies, certain leadership styles were said to be affiliated with positive diverse team outcomes, whereas other studies claimed those same styles led to negative diverse team performance. This made it clear that a more nuanced understanding of the interactions between diverse teams and leadership was needed.

Given that the same leadership styles are said to lead to different outcomes based on different studies, the question remains: what can leaders do to effectively manage diverse teams? If a diverse team is functioning well, what can a leader do to encourage the teams’ continued progress? Or conversely, if a diverse team is embroiled in conflict, how can a leader intervene in order to turn things around? Essentially, which competencies do leaders need in order to adapt and appropriately respond to their teams’ needs?

Step 1: Needs of Diverse Teams

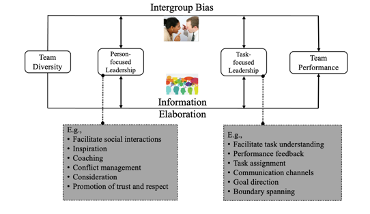

The literature review revealed that there are over 150 different leadership styles, behaviors, and characteristics out there. These leadership styles were then grouped into two big categories: Person-focused leadership and Task-focused leadership in order to make them more manageable.

Person-focused leadership encompasses behaviors like facilitating social interactions, coaching team members, and managing conflicts within a team. Person-focused leadership is very much focused on making sure that all people with a team feel trust and respect towards one another.

Task-focused leadership, on the other hand, is about clarifying the teams’ task at hand. Task-focused leaders emphasize goal direction, facilitate task understanding, provide performance feedback, and generally make sure that their teams have access to whatever resources needed to perform the best they can.

Needs by Leadership Framework: Adaptation is key

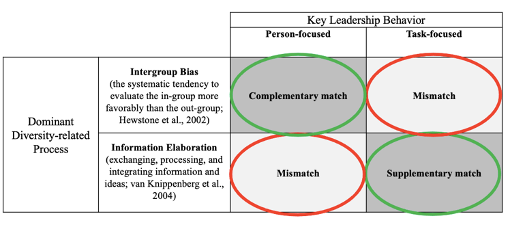

As noted earlier, diversity can be a double-edged sword. Similarly, both person-focused leadership styles and task-focused leadership styles can be either beneficial or harmful to team outcomes; neither style, in isolation, is appropriate for all types of teams, at all times. Instead, the best leaders will be able to adapt to the leadership style most appropriate for their teams’ current needs. When managing diverse teams, adaptation is key.

It primarily comes down to a leaders’ ability to sense whether or not their team struggles with intergroup bias (a symptom of negative diversity-related processes), or practices informational elaboration (a symptom of positive diversity-related processes). If a team experiences intergroup bias, we argue that person-focused leadership is a complementary match. Leaders who are person-focused can solve intergroup conflicts, foster trust, and rejuvenate feelings of respect and appreciation within the team. Leaders who successfully embody person-focused leadership behaviors can therefore help their teams navigate diversity from a negative process into a positive process.

As for teams that experience information elaboration (behavior that we want to encourage), the findings would argue that leaders should adopt a supplementary task-focused leadership approach. After all, you don’t want to change what the team is doing, because the team is already exchanging information in a positive way. In these cases, you want to make sure that the team has a good idea of what the task is, what their goals are, and how they are able to reach their goals. Clarifying the teams’ tasks helps ensure that the teams’ pre-existing communication channels don’t break down due to lack of consensus or direction.

As for teams that experience information elaboration (behavior that we want to encourage), the findings would argue that leaders should adopt a supplementary task-focused leadership approach. After all, you don’t want to change what the team is doing, because the team is already exchanging information in a positive way. In these cases, you want to make sure that the team has a good idea of what the task is, what their goals are, and how they are able to reach their goals. Clarifying the teams’ tasks helps ensure that the teams’ pre-existing communication channels don’t break down due to lack of consensus or direction.

Now that we have looked at how intergroup bias responds well to person-focused leadership, and how information elaboration responds well to task-focused leadership, what about the inverse: how does intergroup bias respond to task-focused leadership, and informational elaboration to person-focused leadership? Well, research indicates that these pairs are mismatched.

For example, if you look at teams that experience intergroup bias, we know that not handling conflict can lead to conflict escalation. And we also know that if you fail to resolve interpersonal conflicts and proceed to set team goals and directions, team miscommunications can arise- that is, if the team members are even talking to each other in the first place!

Similarly, with teams that experience information elaboration – that is, teams that are already in the habit of exchanging ideas and discussing different perspectives – leaders that adopt a person-focused leadership style and try to instigate even more trust and more cohesion can actually foster groupthink and conformity pressure. By itself, person-focused leadership isn’t necessarily bad, but it can potentially make a diverse team suffer if it makes people no longer comfortable discussing divergent perspectives and ideas.

Step 2: How to Functionally Match? (or how to know what to do when?)

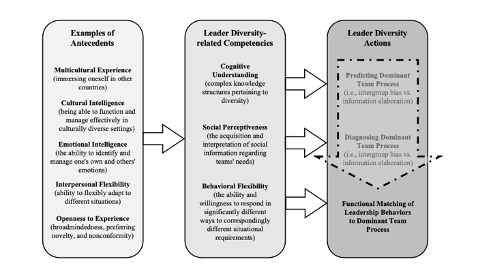

Clearly, matching leadership style to team needs is important. But how can leaders know which leadership style to use and when? Just having person-focused leadership or task-focused leadership in your repertoire doesn’t necessarily mean that you can use it flexibly and in an adaptive fashion. Indeed, leaders need more than these behaviors; they need diversity-related competencies. Diversity-related competencies can help leaders predict what their teams will need and diagnose what is going on in their teams. Only then will they be able to effectively match their behaviors to what the team needs.

Leadership Competencies

The research identified the following three diversity-related leadership competencies:

- The ability to predict how a teams’ diversity characteristics may influence their processes and outcomes (requires a cognitive understanding of both integral bias and information elaboration)

- The ability to diagnose what is currently happening on a team (this requires the social perceptiveness to detect instances of integral bias and information elaboration within a team)

- The ability to adapt according to the needs of the team (requires behavioral flexibility in order to shift to person- or task-focused leadership styles when necessary).

Cues to Predict and Diagnose

Let’s consider the first leadership competency: the ability to predict. What kinds of environmental cues can you use to predict what could happen to your team?

First, you could consider how diversity characteristics – both visible (such as race, gender, age) and invisible (sexual orientation, personality, level of education) – are distributed across team members. The more varied the diversity characteristics in a team, the harder it becomes to identify subgroups within a team, and the more likely it is that teams will engage in information elaboration. Conversely, if a teams’ “diversity faultlines” can be perceived, this can lead to an us-versus-them mentality and can breed integral bias.

Second, you could consider the team’s history. Has this team worked together previously? If so, did they run into any conflicts due to their differences? How are they working together now? Social perceptiveness is extremely relevant here, because you’ll need to focus on the team’s verbal and non-verbal interactions. This can be especially challenging lately, as it’s difficult to pick up on social cues remotely over Zoom. Nevertheless, keep your eyes out to see if certain people are grouping together, or breaking away. In meetings, how is everyone’s body language? Are people interrupting each other? These are things that you can use as a leader to diagnose the dominant process within a team.

Third, there is also a temporal element to consider. After all, teams change over time. Some changes are expected, such as personnel changes. As team members come and go, this could change the diversity composition of the team, which thus might require a different leadership strategy. Other changes are unanticipated, such as team failures. Bruised egos may revive past team conflicts, or reveal a teams’ long-enduring, unresolved biases. An effective leader will need to address both kinds of changes when they arise.

In short, effectively managing diverse teams requires a lot of leaders. They need to constantly adapt their approach to what is going on within the team.

From Characteristics to Competencies to Action

With the ideal leadership characteristics and competencies outlined above, Astrid and her colleagues turned their attention to determining how leaders can develop these competencies, or how to select leaders with these competencies. The findings suggested 5 antecedents.

Firstly, we found that le aders who have had multicultural experiences – i.e. leaders who have previously studied or worked abroad and immersed themselves in a foreign culture – tend to have a greater appreciation for diversity, and also tend to be more perceptive of the types of diversity processes present in teams. Leaders who’ve had multicultural experiences also tend to be more adaptable in their behaviors.

aders who have had multicultural experiences – i.e. leaders who have previously studied or worked abroad and immersed themselves in a foreign culture – tend to have a greater appreciation for diversity, and also tend to be more perceptive of the types of diversity processes present in teams. Leaders who’ve had multicultural experiences also tend to be more adaptable in their behaviors.

Intelligence is also important – particularly emotional intelligence. If you’re able to understand your own and others’ emotions, and you can manage your emotions, you’re also likely good at detecting the emotional currents in your team. As a result, emotionally intelligent leaders are better able to diagnose what is going on in their teams.

Finally, certain personality traits -such as “openness to experiences” – are particularly useful when dealing with diverse teams. Similar to those who have had multicultural experiences, leaders who are open to new experiences tend to have more cognitive understanding, more social perceptiveness, and are more flexible in their behavior.

Three Implications/Conclusions

First, leaders should not adopt a ‘one size fits all’ approach. Second, teams afflicted with intergroup bias – a negative diversity process – require more personal-focused leadership, whereas teams that enjoy information elaboration – a positive diversity process- are well-served by task-focused leadership. However, it’s also important to note that teams constantly fluctuate, and leaders must be prepared to switch between leadership styles as needed. Truly effective leaders must be able to both predict their team’s needs, as well as diagnose their team’s current behaviors and react accordingly. Finally, some of the competencies and traits to develop or recruit for when appointing a leader for a diverse team were highlighted. Great leaders will need cognitive understanding, social perceptiveness, and most importantly- behavioral responsibility.

Question and Answer

How do your findings relate to agile organizations that have rapidly changing team dynamics?

That’s an excellent question. Even if your team – and the role you play within that team – fluctuates daily, the important thing is to not focus on the team, per se, but rather to focus on the sorts of diversity-related processes happening within a particular team. As a team member, you can still diagnose what’s going on, and work with your fellow team members to address team conflicts and move towards a culture of information elaboration.

Can organizational values influence whether or not diverse teams develop positive or negative processes?

Most definitely. It’s not just the leader, but it’s also the organizational culture that influences the nature of diversity in teams. For instance, consider organizations whose reward structures create competitive cultures by pitting teams against teams, or by encouraging employees to focus on their own individual outcomes. Organizations that value inter-group competition can exacerbate the negative processes of diverse teams, because people are not incentivized to share or discuss information. Conversely, organizations that value collective achievement – that say, “We’re all in this together!” – really help to stimulate information elaboration, which is, of course, linked to positive team outcomes.

We’ve discussed the role that leaders can play in fostering effective diverse teams. But what role can team members play? How can we ensure that our organizations foster environments where people feel free to be their full selves at work?

Leaders should focus on making sure that everyone feels included. However, sometimes, it can be hard for leaders to detect who might be feeling left out, especially if they are too focused on a teams’ visible diversity characteristics. Rather, leaders should dedicate their focus to studying the processes and interactions within the team. Do you sense that the team is uncomfortable interacting together? Are there certain people who don’t speak up? These can be more telling in diagnosing negative team environments.

Training all leaders to develop these leadership competencies seems like a daunting task. Could we potentially leverage a specially trained team of diversity consultants instead? And if so, do you have any recommendations as to how we could detect which teams need help?

Issuing periodic surveys could help. These surveys could help track how individuals feel within a team over time. You could consider asking question such as, “Do you feel included in your team? “Is there mutual trust between team members?” “Is there a lack of cohesion in the team?” “Does your team listen to each other’s’ viewpoints?” “Do you feel listened to?” Then, based on your teams’ responses, you can diagnose the type of leadership style they need and then train someone to work with the team can solve these processes. So, it’s not that you have to train everyone, but rather you’d have a set of individuals who have expertise in this.

Has anyone done any work on measuring a correlation between innovation/creative problem solving and team diversity?

The correlation is pretty close to 0. It’s the moderating factors – such as leadership of team diversity – that influence positive or negative correlations.

This is a fascinating conversation. It seems like if the dimensions of diversity can really be about anything – is it really more about the types of perceptions about diversity? And should we think about classifying those? Maybe modes of thinking about diversity vs. thinking about types of diversity.

Let’s start with the perception question. There have been quite some people, for instance Lindle Greer, wh say that you shouldn’t look at the objective things that you can measure, because we always measure the wrong things. Because we assume that what we see are what other people can see as well. So I agree – that moving into the perception corner is more important. That is your own perception, but also perceptions of others. What people see. Who I am doesn’t have to match of what I see of myself.

For example, I’m really very aware that I’m not the only non-US based person right now. This makes it really salient to me, next to the fact that English is not my native language, but all these things are very salient to me. But if I asked you, you would not use that as a distinction. Maybe you would focus on something else, you might pick another diversity characteristic. So, I do agree that perceptions are the goal, and move away from always talking about the different types. Because sometimes people don’t identify with the type of diversity that you categorize them in. That’s a potential problem.

If fault lines are the type of thing that is causing the problem those might be simpler to detect in a survey. One could ask for example, ask whether on your team, it feel like there are in groups and out groups

The fault lines are interesting. Measuring diversity is interesting but it risks objectifying the characteristics. There has been work on fault line activation. Fault lines don’t have to have a negative effect. What is interesting about diversity is that it is important that you do see it if you want to make use of it. You want to see people as unique, different individuals. Maybe fault lines even help with that, because they stress that people are different from you. And if you’re able to handle those differences, you can make use of them. I would say that yes, up to a certain degree fault lines can have a negative impact, but not always. It’s best if they’re there, and the team doesn’t see them as a problem, but rather, as an interesting aspect of the team.

I was also interested in power differences diversity in teams solving complex problems. What happens to sharing of insights, information or ideas when there is a power dynamic in the group?

A lot of the types of diversity we talk about are associated with status, or power to begin with. People have very clear images in their mind of high power vs. low power groups (i.e. men might be seen as being in a higher power group to many, we know that in the socioeconomic status, such as the way you speak, can be a very strong indicator of whether you are from a higher class group or a lower class group). And that all has, of course, an impact. We also know that lower status people and lower power people tend to speak less, they are more inhibited in their behaviors, and yes – in a situation like this, if you feel like you have less power, you’re also less likely to speak up. In the case you mentioned, a lower “power” person might be worried that people who are higher powered have a certain opinion of you and you don’t share your thoughts. I do think that’s a very important diversity characteristic. But maybe perceptions are more relevant there, too, than actually thinking about what is high vs. low power for y

Add a comment