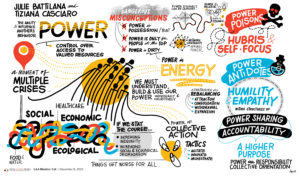

Summary of LILA Member Call with Julie Battilana: Power for All: How it really works and why it is everyone’s

December 2021

Notes by Marga Biller

Introduction

During the October gathering, we explored what agency looks like and what practices might lead to greater agency for all. Among the puzzles we identified was the connection between agency and power. To help us deepen our understanding, we invited Julie Battilana to share her research with the LILA community. Julie is a scholar, educator, and advisor in the areas of social innovation and social change. She is a both a Professor at the Harvard Business School and Professor of Social Innovation at the Harvard Kennedy School. Julie has recently published a book titled Power for All: How it Works and Why it’s Everyone’s Business with her co-author Tiziana Casciaro.

To listen to the recorded presentation click here.

Introduction – Why Write this Book and Why Now?

On a global level, we have been facing a major health crisis related to the pandemic as well as a social and economic crisis that is characterized by deepening inequalities and an environmental crisis. If we trace the roots of this multi dimensional crisis, the exclusive focus on financial value maximization has been associated with the deepening of inequalities and further destruction of the planet. We are at a point where if we “stay the course” we will further increase inequalities. What we’ve learned from all the work in social sciences is that when you reach levels of inequality that are extreme, everyone is impacted. The people at the “bottom” suffer as well as those at the “top” because communities characterized by higher levels of inequality are not as healthy as equitable ones. They are not safe and they are create an environment in which economic productivity is not as high. This means that we have to reinvent our social and economic system.

If we really want to reinvent our social and economic system, we need power because power is the ability of an individual or group of individuals to influence other people’s behavior. Julie shared that she and her colleague Tiziana Casiaro wrote the book now because it’s absolutely critical for us to understand the power we have and how to use it for the kind of positive impact that we need.

What is Power?

According to Battilana, your power is all about your ability to influence other people’s behavior; but that isn’t the whole story. Battilana’s research identified three main misconceptions about power:

- Power is a possession. There is a misconception that powerful people have some traits that make them powerful, for example, charisma.

- Power is only for people at the “top.” The second misconception about power is this idea that power is only for the people at the top; it’s only for the presidents, top executives, CEOs, Prime Ministers, generals, etc.

- Power is dirty. The third misconception is this idea that power is dirty.

If you combine these misconceptions when you ask indivivduals about power, they tend to say things like – I don’t have the personality traits. And anyway, I’m not one of the people at the top, but good for me, because at least I’m not getting my hands dirty.

Where Does Power Come From?

Power resides in control over access to valued resources. For example, if as a leader you control access to budgetary resources that an employee needs and wants to get their project done, then you have power over them. But power dynamics are not that simple. If that employee has a strong connection to a person whom you want to bring into your group because their work is particularly important, then that employee also has some power over you. What this illuminates is that power is relational – it’s always relative. Power dynamics are not static; they shift over time, so having a keen understanding of the dynamics is important if you are to facilitate systemic change.

An Illustrative Story

Julie shared the story of Zuma who was born in a remote rural area of Tanzania. When she was a young girl her dream was to become a teacher, but she was not able to go to school. She spoke about how for most of her life she felt quite powerless because, at the end of the day, most of the decisions in the village were made by the powerful members of the council. To her knowledge, no women had ever been a member of the village council. In 2016, Zuma’s situation radically changed and she went from feeling powerless to becoming one of the most powerful members of the community. This happened when she was trained by an NGO called Barefoot College that enabled illiterate women across the global south to become solar engineers. The five-month program is based on learning by doing and peer to peer learning. Barefoot College explained to the villagers and to the village council that by training solar engineers they would get all the equipment to bring electricity the village. Even the members of the powerful console immediately understood that it was a great opportunity and they had to push for that to happen. Zuma’s husband initialy resisted the idea, but was convinced by the powerful members of the village council and the representatives of Barefoot College who worked out an arrangement with him that would enable him to go visit his wife regularly during the time that she would be going through the program. After five months Zuma came back to her community and she built an electricity supply for the community. She thus became one of the most powerful members of the community, and was in control of one of the most valued resources in the community – electricity.

In this example, the valued resource was electricity and control over this resource was a source of power. In other situations we may value a whole set of psychological resources such as affiliation achievement, status, or morality. For example, Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, Malala Yosufzai, or Greta Thunberg are leaders who exemplify moral values that some of us want to be associated with, and that gives them a great deal of power over us.

So back to what is power: Yes, it is about control over and access to valued resources, but these valued resources do not necessarily have to be money or tangible resources. These valued resources can also be morality, achievement, affiliation, etc.

The Agency and Power Connection

Battilana reminds us that as leaders, it is our responsibility to demystify the aforementioned misconceptions, as they have implications on individual and collective agency. If you don’t understand power, you cannot have the desired impact within your community or within your organization. When this happens people tend to leave it to others to decide for them and these others then concentrate ever more power in their hands, thereby reducing individual agency. Battilana’s research finds that what when people understand power dynamics, they become much more effective leaders and change maker. You can help people better understand power and the power dynamics around them.

When we fully understand the fundamentals of power, we are equipped to debunk the power myths and misconceptions, and we’re also equipped to help others debunk these fallacies. Think about the Zuma story. The first misconception Battilana spoke about – power as a possession- and her characterization that it is, instead, relative. Zuma didn’t have much power at the beginning but she gained a skill and the skill as a solar engineer gave her power in the context of her village. It wouldn’t have given her power in just any kind of context. Consider the second fallacy- the idea that power is only for the people at the top. When Zuma came back and equipped the village with electricity, she was not yet a member of the council, and yet she had a great deal of power. And now to the third fallacy, the idea that power is dirty. Power itself is not inherently dirty. The reality is that power is just the energy that you need to get anything done. It’s about influencing other people, which is about their behavior.

Power Poisons and Antidotes

Battilana cautioned that in some instances power can in fact be be dirty. What we’ve learned from history, from our own experiences, and from research -especially in social psychology- is that power has two very insidious effects on our human psychology.

- Hubris – a sense of invisibility. When we start thinking that we deserve to be in positions of power, that we are better than others, that we are right to be confident in our abilities because we can do pretty much everything, then we start having the sense of invincibility. This is the main trap of hubris.

- Self-centerdness. When we are in positions of power for a longer time, we can become more self-centered – unable or unwilling to put ourselves in the shoes of others. We start thinking about everything through our own lens.

Research has found that there are power antidotes. The antidote to hubris is the practice of humility, which is the absence of pride and arrogance. Practicing humility requires an awareness of our impairments. The antidote to self-centeredness is empathy, which requires an awareness of our interdependencies. We know that when we cultivate humility, when we are empathetic, we are able to embrace a higher purpose, to think of our power as a responsibility and cultivate a collective orientation. As leaders, we must do this for ourselves and also enable others around us to cultivate humility and empathy within the cultures of our organizations.

Julie shared the example of Vera Kojiro a pediatrician and founder of Instituto Dara in Brazil who wanted to do something about the number of children from the poorest communities who were unwell and either didn’t make it to the hospital in time or whose parents couldn’t afford the medications that would save their lives. The Insituto helps these families deal with employment issues, with healthcare issues, as well as with housing issues, and this multi-dimensional intervention has been very effective. As Vera’s work became well known, her employees began sharing feedback that she no longer acted with humility and empathy. In order to change the situation, Vera instituted new routines that enabled others to question, to voice their opinions. She also changed the processes and systems in the organization to do two things – to ensure power sharing and accountability. For example, Vera reorganized the weekly meetings, and made it clear that she would be the last one to speak, that everyone would have equal time to express their concerns and share their ideas. If she interrupted, she would have to be held accountable and participants could call her out. Power doesn’t have to be dirty if we practice humility and empathy. If we create the processes and systems in our organization to enable people to practice humility and empathy and if we also create and nurture the structures of power sharing and structural accountability, we can hold those in power accountable to make sure that there is no power abuse.

Collective Power

When we come together with different sources of power we gain collective action in organizations and in society, which can enable systemic change. If we look at social movements, we see a lot of agitation for change; but that is not enough to make change happen. Agitation is critical, but we also need to innovate and orchestrate for any kind of change to be sustainable. Think about the Occupy Wall Street movement where there was high agitation, but the movement slowly died because they didn’t have innovation.

Battilana identified three critical roles for change to take hold- agitators, innovators, and orchestrators. Agitation without innovation is a set of complaints without a way forward. And innovation without orchestration means the loss of a potentially great idea.

- Agitators are those who speak out against the status quo and raise public awareness of the problems.

- Innovators are the ones who developactionable solutions to address the grievances identified by agitators.

- Orchestrators enable the coordination of all the parties involved to put in place the changes that allow the solution envisioned by the innovators to be adopted at scale.

Closing

It is an unpleasant but acknowledged fact that in organizations, as in society, we are not all equal. There are existing power hierarchies that constrain some of us and enable other. However, once you understand the fundamentals of power, you are able to better understand the power hierarchies and then you can speak about what we can do together to dismantle unjust power hierarchies.

Battilana shared that the book is titled “Power for All” because we must understand, build, and use our power individually and collectively as citizens if we want to be able to identify and prevent power abuses at a time when we have to be very careful not take democracy for granted.

Questions and Answers

Q: If we feel constrained by the power hierarchy in our organizations, and we want to redistribute power as a way to make your organization more inclusive how might we start?

JB: Julie shared the example of Elena Shu from NASA who was the first Latina American astronaut to go to space. She later became the head of the Johnson Space Center and made innovation and inclusion her two priorities . She knew that if she truly wanted to share power and to make the organization more inclusive, offering diversity training would not be enough. She also knew that just trying to promote a few members of minority groups would not be enough. She was very systematic in her approach – creating a council and a committee inviting people from across the organization and across the levels of the organization to be part of the committee. She asked the committee to work with her to review all of the processes and systems in the organization that had an impact on the allocation of resources. They reviewed promotion and recruiting processes; for example, they analyzed how resources were distributed and addressed biases to ensure a fairer distribution of the value of resources. She didn’t stop there.

Going through the formal processes is not enough. You also have to account for the informal processes that actually affect the distribution of resources and make informal opportunities available to some and not to others. Elena created a program called “talk” that was all about making these informal opportunities transparent so that people would know about them, and would be encouraged to raise their hand and have access to the opportunities.

Rather than starting with “how do we get it done?”, go at it directly and think about how the resources are currently distributed. Once you have the data, then you are ready to tackle “what can be done in order to have a fairer distribution of those resources? What are the processes and systems which we need to change? And what are the informal processes and formal norms that should evolve if we want that to happen?”

Q: What do you do when the ground is shifting underneath you and your tools to exert power aren’t the same anymore?

JB: What you are getting at is what do you do when the the norms are changing, the rules of the game are changing and and you don’t have as much power as you did. The first thing is be aware of it, what is it that people value? If we go back to Trump’s election he certainly understood what is what that his electorate valued, and that’s what he offered them in the speaches that he gave. He would state that he was giving them back the power they had lost. You don’t make assumptions, instead you put yourself in their shoes so that you get to reassess and understand what they need and want and then once you understand that you can be thinking about who can I partner with? What do I need to learn, so that I can then engage with them. Let me be even more specific and say to you the following. Once you understand those fundamentals of power, you also get to understand that they are four strategies you can use to rebalance power in any situation.

- I can try to convince you that what I have is more important to you than you ever imagined. I know you don’t care that much, but maybe I can convince you that you should care.

- Consolidation strategy. At the moment, I may not have much power because maybe there are many other people who can offer it to you but I have by bonding together to unionize for example, we’re clear about the conditions we want to use.

- To reduce the power that the other party has over you. You turn your back and withdrawal and you reduce the power that I have over you significantly.

- In this case, you know that you have something that I need, but I’m going to go and look for alternatives to you.

These are all strategies that anyone can use in any organization to rebalance a power relationship. In order to use them you first have to understand the power imbalance and then use the fundamentals of power.

Q: It seems like if you have power, you can use that power to collect more and more resources forever. Wouldn’t it have to be the case that the people with power have to enable other people to get power?

JB: That is exactly what happens in the existing power hierarchies and how they are reproduced. Think about racism and paternalistic cultures that are power hierarchies for example. Human beings are very good at telling stories and we use stories to legitimize a certain distribution of power. Those at the top have access to evermore resources and that produces the two psychological effects. They think they deserve the power, they don’t put themselves in the shoes of others and they are more prone to taking action. This is a perfect recipee to accumulate ever more resources. In that way, they reproduce the status quo. And to make it even worse, the people at the bottom also contribute to the reproduction of the status quo. We know thatthis type of power reduce agency and leads people to think they probably deserve to be where they are in that system. How can you change this? From social movements we learn that when people get together and demand change, its not only the people at the bottom who see that change is necessary. Others begin to understand that things are not acceptable and do not want to be associated with the status quo. What leaders have to understand is that continuing this cycle is not tenable. More and more top executives in companies realize and understand that sharing power is not a sign of weakness, that actually, sharing power may well be the best way to motivate your employees to give them the autonomy and agency they want, so that we can together accomplish more.

Q: So often as you see in revolutionary movements, people start off with a firm belief that they are going to take over the power and change it. And then oftentimes, they start replaying the same things that they wanted to affect. How do we ensure that voice and agency are kept front of mind?

JB: In order for employees to have a voice, two things need to happen – a structural change and a cultural one. On the structural side, we can learn from the German governance model. Many workers are entitled to have a seat as representatives on the board of companies. If we are in a world in which only shareholders are present on the board of companies, by design we will reproduce the power imbalances. So the question is – will employees have a real voice and be entitled to have a say in all of the critical strategic matters that are related to the life of an organization? For that to happen in a constructive way, the culturesof the organization has to change. I propose that for us to work well together we need to think about how we share power in order to accomplish our overarching goals. There are companies today that are using inspiration for these different models like the governance model Germany, to integrate aspects of what they have been doing and reinvent their companies. With the employee revolution, it is clear that employees don’t want a world in which they don’t have a say about the working conditions and the future of their companies. They want to be proud of the companies that they are a part of. Eventhough workers have a great deal of power in the market now, they still do not really have a voice or not a voice that matters. This is why we have to move beyond the current models and we need to move forward on all of the dimensions at once. There is an environmental crisis we have to tackle, we have to tackle it together while respecting human beings. We should stop commodifying work and enable people to bring their best selves to their organizations and to thrive.

Q: I am curious whether there are insights from research that you’ve gleaned as it relates to how technology is shifting how humans either distribute or manage power?

JB: Power is about control over access to valued resources. We live in a world in which a few companies have access to information about us. The use of technology therefore raises a set of questions. If we are going to build trust into these systems, we will need to regulate them. The thing we will need to do is focus on protection of our personal data. As citizens and leaders of organizations, we ought to be thinking about what’s the right balance. The other point is on the AI front and the use of algorithms- how do we get organized to make sure that things are more transparent. Regulating in that domain is complicated, because it raises a lot of difficult questions about what’s a fair algorithm and what’s not? What kind of data are we using? In writing the book we interviewed many people who want to help build the trust into the technology and make sure that we use technology for good. I think we what we need now is to be part of the movement to create the kind of context in which we can then know that technology is used not to reinforce the existing inequalities, but to address them. I don’t think we’re there yet but we are in a moment when eeryone is realizing that we have this amazing technology that’s supposed to distribute power to all but clearly this is not what has happened. All the leaders of industry have a key role to play in partnership with the government and the social change makers.